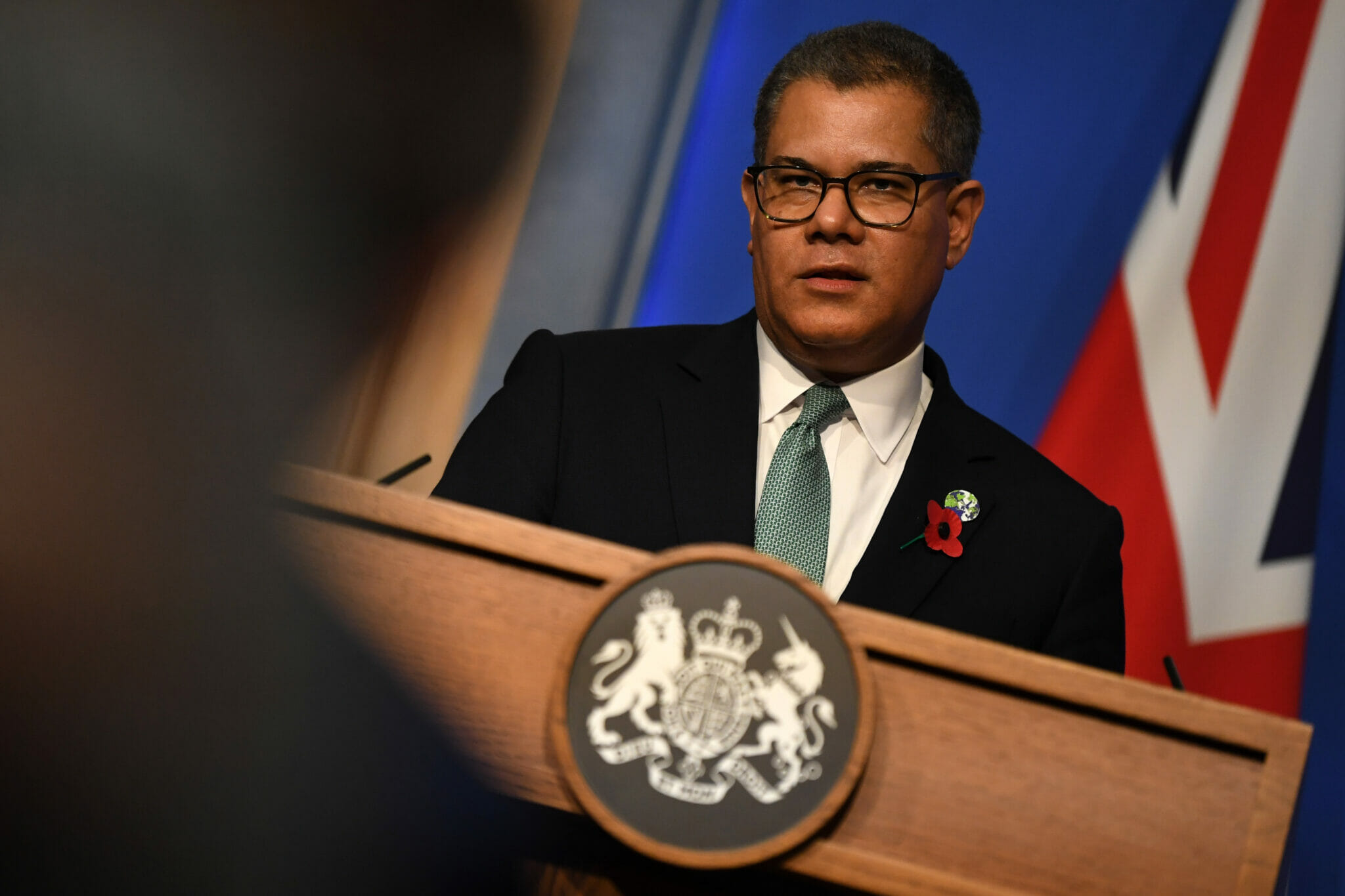

GLASGOW, SCOTLAND—COP26 president Alok Sharma held back tears as he accepted India’s last-minute motion to weaken the summit’s pledge to “phase out” coal. Sharma had been saying for months that he wanted COP26 to “consign coal to history.” And until India insisted otherwise at the eleventh hour, it looked like the summit might achieve that scientifically imperative task.

But United Nations climate negotiations operate by consensus: Each of the 197 participating nations can veto the majority. In effect, India—with China’s support—had threatened to block the agreement entirely if the text was not softened from “phase out” to “phase down” coal.

Moments after Sharma gaveled the Glasgow Climate summit to a close on Saturday, this reporter asked if he had tried to talk India out of its explosive last second demand to weaken the summit’s pledge. Did Sharma, as the summit’s presiding officer, try to dissuade India from this hostage taking?

A plainly weary Sharma declined to divulge his conversations with the delegations, but said, “Anyone watching the footage can make up their own minds about how I felt.”

“It is emotional,” he added. “I have visited frontline communities around the world who are experiencing the effects of climate change. I’m disappointed we couldn’t get that language across the line.” Still, the COP26 president said, this was the first time in the history of UN climate negotiations that a coal phaseout was even mentioned in the agreements that governments signed.

It’s impossible to be happy about COP26’s outcome—virtually every country said the Glasgow Climate Pact was less than it wanted, and island nations in particular were furious over India’s last second intervention—but the pact was not an irredeemable failure. Sharma’s claim that COP26 had “kept 1.5 alive” is plausible, if barely.

One reason why is that the pact obliges the world’s governments to come back next year and try again—and bring stronger action plans with them. A second reason pertains to a recent climate model that remains little-known among the public, the press, and even many policymakers and could fundamentally shift our thinking about what’s possible: Contrary to widespread belief, there is far less additional temperature rise irrevocably “baked in” to the climate system than the three to four decades that was previously believed. Fast, dramatic emissions cuts can therefore still make a big difference.

The provision urging countries to develop more aggressive climate action plans before COP27 markedly accelerates the schedule that existed prior to COP26, when the world’s governments were not due to update action plans until 2025.

“Scientists have found that governments’ current action plans would cause global temperatures to increase to 2.4 [degrees] C, which would bring absolute devastation to hundreds of millions of people and ecosystems around the world,” Jennifer Morgan, the executive director of Greenpeace International, said in an interview at COP26. “So waiting five years to come back to the table is not an option.”

What’s more, next year’s updated climate action plans must outline what governments will achieve during the 2020s—the so-called “decisive decade” when global emissions must be cut in half to limit temperature rise to 1.5 degrees C—rather than by 2050, the date referenced by many government “net zero” pledges. And United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres went further, urging that action plans be updated “every year” throughout the 2020s while also “raising ambition.”

Requiring annual updates could encourage stronger action around the world, said Guterres and other civil society leaders. Annual updates would expose developed countries, fossil fuel states, and other foot-draggers to more frequent and sustained pressure from developing countries, which generally want more climate action, as well as from the media, activists, Indigenous peoples, religious leaders, and other elements of civil society.

Sending “a message of hope and resolve to … all those leading the climate action army,” Guterres said after COP26 ended that “I know many of you are disappointed.” The secretary-general added that, “We won’t reach our destination in one day or one conference. But I know we can get there…. Never give up. Never retreat. Keep pushing forward. I will be with you all the way. COP27 starts now.”

Pushing forward with the ambition of capping average global temperature rise to 1.5 C need not be an exercise in futility in light of scientists’ updated understanding of the climate system.

For decades, scientists thought that even if greenhouse gas emissions stopped overnight, the inertia of the climate system—in particular, carbon dioxide’s long-life span in the atmosphere—would nevertheless keep driving global temperatures higher for at least 30 more years. But Scientific American recently explained that this is “an old idea” that scientists have discarded. “As soon as CO2 emissions stop rising,” the magazine explained, “the atmospheric concentration of CO2 levels off and starts to slowly fall because the oceans, soils and vegetation keep absorbing CO2, as they always do. Temperature doesn’t rise further. It also doesn’t drop, because atmospheric and ocean interactions adjust and balance out.”

Kevin Anderson, a professor of energy and climate change at the University of Manchester, affirmed the Scientific American analysis.

“It’s now well-established in the scientific community that if we stopped all emissions today, we would stop almost all of the temperature rise and most of the resulting impacts,” Anderson said.

The problem is that governments at COP26 were not acting on what science says, Anderson added.

“Science tells them, if we want to hold to 1.5 [degrees] C, what we need is rapid, deep cuts in emissions,” he said. “But there is absolutely no sign of that from the negotiators here. So, they are explicitly choosing to fail poor people today, who suffer the worst impacts of the climate emergency, as well as the young people who have to live with this in the future.”

“The difference between 1.5 and 2 degrees [C] is a death sentence for us,” Aminath Shauna, the Maldives’ minister of environment, climate change and technology, told the summit after India insisted on weakening the coal phase-out pledge. India had justified its position as a balanced and pragmatic approach that recognized that some developing countries still relied heavily on fossil fuels. Shauna responded, “What is balanced and pragmatic to other parties will not help the Maldives adapt in time. It will be too late.”

Meanwhile, Jennifer Morgan of Greenpeace vowed that she and fellow climate justice activists around the world “will be back in the streets starting Monday.”

“We will be pushing governments to phase out not just coal but all fossil fuels and be much more ambitious in general,” Morgan said. “So when governments come back to these negotiations next year, they’ll bring climate action plans that actually match the climate emergency.”

Mark Hertsgaard is the co-founder and executive director of Covering Climate and the environment correspondent for The Nation.