Pope Francis may have been a climate trailblazer, earning himself the moniker the “climate pope,” but he’s far from alone: Leaders across many faiths joined him in advocating for urgent action on climate. Globally, faith communities are playing a powerful role in promoting environmental stewardship with land conservation and tree planting projects and addressing climate change by transitioning to renewable energy, divesting from fossil fuels, and organizing community-driven sustainability efforts.

In this one-hour press briefing, co-hosted by Covering Climate Now and partner outlet the National Catholic Reporter, we dug into how faith communities are tackling climate change. Panelists included Dr. Iyad Abumoghli, director of the Faith for Earth Coalition at the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), and Reba Elliott, the head of advocacy at Laudato Si’ Movement. Brian Roewe, lead reporter for EarthBeat, a project of the National Catholic Reporter, moderated.

Panelists

- Dr. Iyad Abumoghli, director of the Faith for Earth Coalition at the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP)

- Reba Elliott, head of advocacy at Laudato Si’ Movement

Brian Roewe, lead reporter for EarthBeat, a project of the National Catholic Reporter, moderated.

Transcript

David Dickson: Hello and welcome to yet another press briefing with Covering Climate Now. My name is David Dickson. I’m the TV engagement coordinator and resident meteorologist at Covering Climate Now. We are so thrilled that you’re here today with us to explore faith-based community climate action. Now, for those of you that might be new to Covering Climate Now, we are a global collaboration of 500 plus news outlets in 60 countries that reach a total audience of billions of people or organized by journalists for journalists to help us all do better coverage of the defining story of our time. We convene discussions like today’s webinar where journalists can talk amongst ourselves about how to tackle common challenges. In addition, we train newsrooms both in English and in Spanish, provide cutting-edge analysis in our climate beat and other newsletters and establish standards of excellence in climate reporting through our annual awards program.

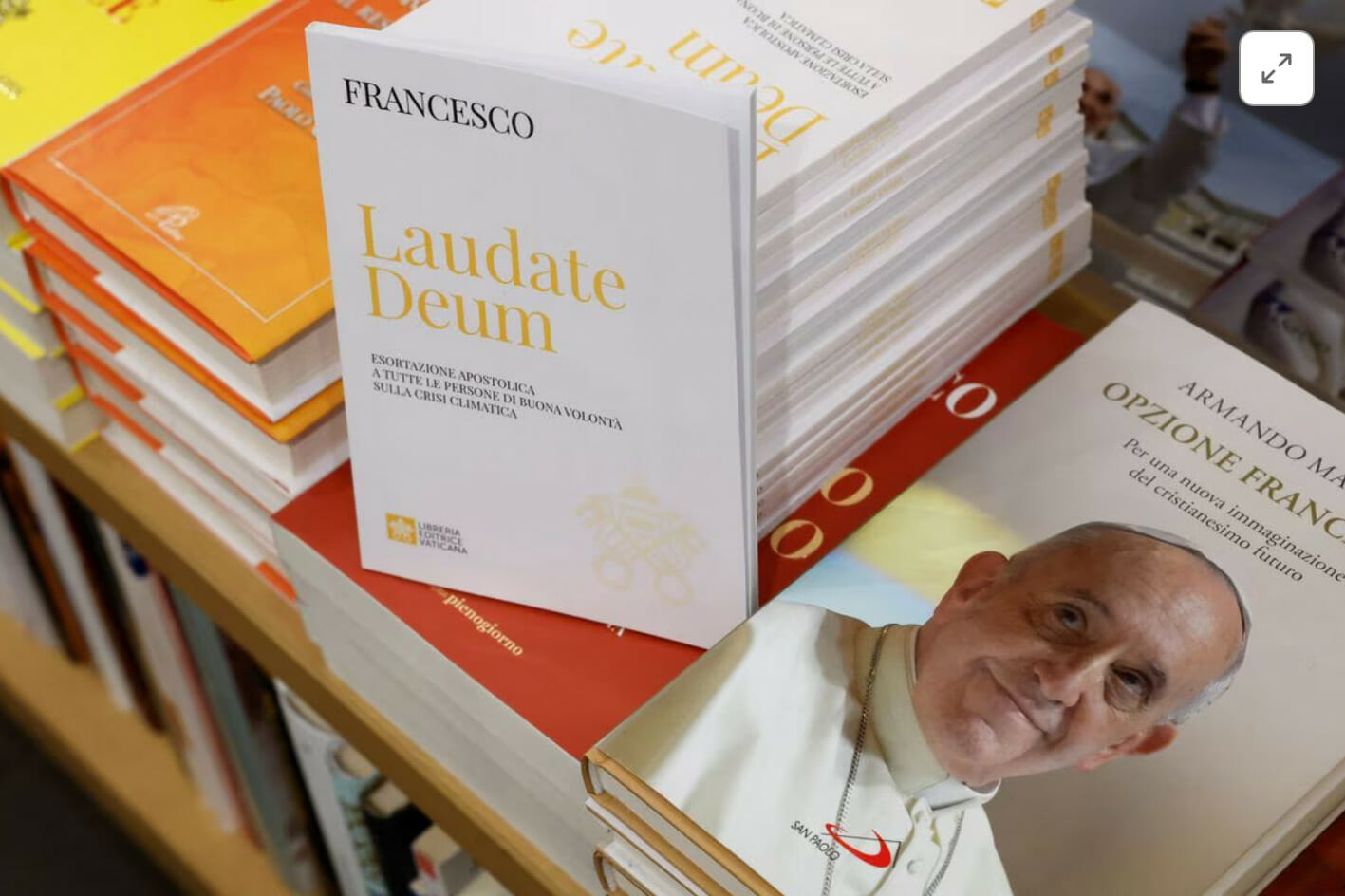

The best thing, all of our services are free of charge. You can go ahead and find more information and apply to join Covering Climate Now on our website, simply coveringclimatenow.org. All right, let’s dive right in. This weekend, May 24th, marks the 10th anniversary of Pope Francis’s groundbreaking papal letter Laudato Si’, Praised Be, in which he appealed to people of all faiths to care for our common home. Francis’ passing last month and the election of Pope Leo XIV has led many to wonder if the new pope will continue to make climate change a priority for the Catholic Church moving forward. While Pope Francis may have been a trailblazer, leaders across many faiths have joined him in advocating for urgent action on climate. Globally, faith communities are playing a powerful role in promoting environmental stewardship and addressing climate change.

We’ll be talking about that work in today’s webinar and to lead us through it, I will pass the mic over to Brian Roewe. Brian is the environment correspondent for the National Catholic Reporter, an independent nonprofit newspaper covering the Catholic Church and is a CCNow partner. He is the lead reporter for EarthBeat, NCR’s vertical on faith, climate change and environmental justice. Over the past decade, Brian has extensively covered the buildup, release and response to Pope Francis’ encyclical letter on the environment. He has reported from the UN Climate and Biodiversity Summits, a Vatican meeting on Amazon rainforests in rural Honduras, and on the connections of climate and migration. Go ahead and take it away, Brian.

Brian Roewe: Thank you, David, and thanks for having us today. Approximately 80 to 85% of people worldwide belong to a religious community. That’s according to most recent studies in polling. The most populous religions are Christianity and Islam. About 50% of Christians or 1.4 billion people are Catholic. The intersection of faith and climate action offers a wide array of stories for journalists to explore. At National Catholic Reporter, we’ve been examining these extensively for the past five years through EarthBeat, our vertical examining specifically the intersection of faith and climate. The United Nations Environment program estimates that faith-based organizations control 8% of habitable land, including 5% of commercial forests. In addition, they operate roughly half of all schools globally and more than a third of hospitals and health clinics and together would represent the third-largest investment group in the world. So lots of avenues and lots of entry points into this story of climate change and faith.

Faith leaders also have a unique opportunity to inform people about the climate crisis by preaching about it and to encourage climate action in their communities as stewards of God’s creation or as Pope Francis wrote in his encyclical letter, Laudato Si’, 10 years ago, to care for our common home. We have a terrific panel joining us today to talk through these issues. In the first half hour, I’ll pose questions to them and in the second half hour we’ll invite questions from our fellow journalists. You can submit your questions via the Q&A button at the bottom of your screen. Please be sure to include your name and the name of your news outlet when you post your question. And while this briefing is open to everyone, please know that we’re taking questions from working journalists only. Now allow me to introduce our panel. First we have Reba Elliott, who is a member of the executive team and head of advocacy for Laudato Si’ Movement, where she brings 15 years of executive leadership to build a movement for this planet our common home.

She’s the impact producer of the feature documentary film, The Letter, and her programs and campaigns have reached 2 billion people in 5,000 institutions. Dr. Iyad Abumoghli is the director of faith for earth coalition at the United Nations Environment Program, where he leads efforts to engage faith-based organizations in addressing the world’s environmental challenges. With over 40 years of experience in sustainable development, policy, environmental governance, Dr. Abumoghli has held various leadership roles within the UN. He is recognized for pioneering interfaith collaboration on environmental action and advancing the role of ethics and values in sustainability. So please join me in giving our panelists a warm virtual welcome. So we’ll start with some questions now. And Reba, I’d like to ask you, as head of advocacy with Laudato Si’ Movement, how are you feeling about the election of the new pope, Pope Leo XIV? What is the early read on him? Are you hopeful that he’ll continue the work of Pope Francis in this space in prioritizing climate change?

Reba Elliott: Oh, that’s a great question, Brian. Thank you so much and thank you to David and Theresa and our friends at Covering Climate Now for organizing this terrific event. It’s such a pleasure and an honor to speak alongside someone like Dr. Iyad, who’s been such a wonderful friend for so many years. Along with you, Brian. Yeah, so about Pope Leo XIV. Yes, we are feeling hopeful and that hope partially rests in Pope Leo XIV himself and partially in the long history of teaching within the Catholic Church that extends beyond him. When Pope Leo was elected, I think all of us were very surprised. Those of us who believe in the Holy Spirit saw the work of the Holy Spirit there, finding a candidate who was not anybody who was expected, but who seemed to be just right for the moment. And you can tell a lot about a person by his relationships and what he’s done in the past.

And we were really surprised to find that members of our movement, our friends and partners, had photos of him from Peru from the early ’90s where he had been with people in small villages standing alongside the most vulnerable members of his community. And those photos continued up until the time he left Peru. And to see all of those pictures come in, people saying, “I know this guy.” It was just a wonderful sign of his really authentic commitment to standing alongside our sisters and brothers in the mud, in the jungle, in the city, wherever we find ourselves. We’re also really thankful to have been surprised that in his previous to becoming Pope, he had retweeted tweets of Laudato Si’ Movement. He had encouraged people to sign the Catholic climate petition before the Paris Agreement encouraging for Paris to enshrine 1.5 in the text of the accord.

So everything that we’ve learned about Pope Leo XIV has shown us that he’s someone who has a real knowledge and awareness of how the climate crisis affects all of us and the poorest and most vulnerable among us above everyone. So we have a lot of confidence in him, but we also have confidence in the fact that popes for 50 years have spoken about the environmental catastrophe. Pope Francis brought these teachings to light with new relevance and urgency for today’s crisis, but it’s in some ways a very old theme for popes and for the Church overall. And so we’re confident that he’ll stand in the line of those decades and decades of teaching and leadership. So following on Pope Francis, but also on the previous Popes as well.

Brian Roewe: Yes, yes. Everyone’s kind of reading the tea leaves of his past to see what he has said or where he might go on environmental questions on climate change. Especially after Pope Francis, we had reporting today that looked at his time in 2023 when he was still bishop in Peru on the ministry, the service he was doing in the aftermath of severe flooding that happened in northern Peru. So we’re all watching in that way. Are there things now that he is pope that you’re particularly paying close attention to or Laudato Si’ Movement is paying close attention to kind of see where he might go or when he might be saying something? I know in the past, popes have issued statements around World Environment Day or some of those UN designated days around ecology and environment. Are there things that you’re watching?

Reba Elliott: Yeah, that coverage in National Catholic Reporter was great, so kudos to you and the team for pulling that together. Yeah, I think that the forest opportunity is probably around the 10th anniversary of Laudato Si’, as was mentioned earlier, is taking place on Saturday 24th of May—Sunday, Sunday 24th of May. And yeah, I think that a statement around that date is a good early sign. There’s also an annual event that takes place in September called The Season of Creation. It’s a global annual celebration of prayer and action for the environment that celebrated not only by Catholics but all Christians around the world. And I think that a statement around that time is something that we would look for. And then of course the Holy See’s involvement in the COP process as a party to the Paris Agreement. It’s interesting to know what the commitment will be like, what their participation will be like this year. I think that all of those things are things that we and many other people will be looking at.

Brian Roewe: Great, thank you. Dr. Iyad, you lead the Faith for Earth Coalition at UNEP United Nations Environment Program and that formed in 2017. What was its genesis and why was the UN interested in religion when it comes to environmental questions including climate change?

Dr. Iyad Abumoghli: Well, thank you Brian, and good morning everybody from the evening in Nairobi. Brian, you might know that in 2015, the leaders of the world have adopted what we call Agenda 2030 and the sustainable development goals. And well, we believe that all the goals contribute to healthy people on a healthy planet, but there are of course certain SDGs that are related to the environment. But SDG number 17 is about partnership and the sort of whole society approach to the implementation and achievement of these goals starting from poverty to education to life above the ground and under the water and what have you. So the whole of society, when you think about it, and at that time when we looked at it, we found that there are several society organizations that are engaged in promoting and supporting governments in the implementation. But rarely you would find a faith-based organization that is geared towards achievement or implementation of the SDGs. And you mentioned it more than 80% of the people associate with religion.

And you quoted some numbers from our reports that they own more than 50% of schools, 8% of habitable land. I mean, look, 8% of habitable land that is 36 times the size of the United Kingdom, that is owned by faith-based organizations. So they have what I call the three powers, the power of convincing, the power of convening and the economic power. Convincing, of course, they have a set of standards, teachings that are centuries old that they can rely on when they teach about how to live in harmony with nature. And convening, look, I mean, millions and millions of people go to churches on Sundays or mosques on Fridays and so on. It’s only a call for prayer that brings people together. And the economic power, of course, there are trillions of dollars being invested by faith-based organizations. So we thought, of course, we didn’t want to create yet another NGO or another advocacy tool.

But as the United Nations Environment Program is the highest authority on environment at the global level, we have our governing body, which is called the United Nations Environment Assembly that meets every two years and adopts decisions and resolutions related to the environment. So we provide the policy arena or policy dialogue where we bring people from different backgrounds. So one of the most important elements was to bring faith leaders and faith actors to be part of that policy dialogue and to impact the policies and decisions that are adopted by politicians. The second thing is that we thought that yes, probably everybody understands that we have to live in harmony with nature. This is what our religions call for. But there was little understanding about the commonality of values among all religions related to living in harmony with nature. So we wanted to bring that knowledge out. So we have published several publications on Catholic or Christianity and disaster risk reduction, Islam and stewardship, Buddhism and interconnectedness.

So we went deep into contemporary environmental issues because environmental issues in general might be understood by the regular people. But when you talk about specific issues like fossil fuel or you talk about climate finance, that is not understood by the regular or ordinary religious follower or an ordinary person. So we wanted to bring that knowledge out. And finally, trying to green the investments of faith-based organizations, each religion has some standards when it is related to investing, their resources, but it is related to no alcohol, no funding of arms or what have you. But there’s nothing about no harm to the environment. So we wanted to bring that upfront into the investment priorities and standards for faith-based organizations. So they also contribute when they green their assets. Imagine greening 50% of schools at the global level that is humongous, and that contributes to reducing, of course the carbon footprint and the impact on the environment.

So this is why the Faith for Earth Coalition was created and to support it at all levels, we created five councils. The first council is the council of eminent faith leaders. Pope Francis was one of the highest faith leaders. We had Imam of al-Azhar, the highest Islam and so on. And then the council of young people, the youth council, because young people have a lot to say and have their energy to implement the goals of the sustainable development goals. We have a woman council because we wanted women voices. We wanted to address gender issues as related to religions, but also as related to the environment. And we have the religion and science council because we wanted to bridge the understanding between the scientific evidence and the religious teaching. And finally a council for accredited faith-based organizations because we have at our board or governing body accredited non-governmental organizations. And when we started, we had none of the faith organizations. And currently we have 90 faith-based organizations as members. So we have created that platform, that forum where people from faith backgrounds can come and discuss policy issues.

Brian Roewe: Thank you for that. You mentioned the convening aspect of bringing religious leaders into conversation with policymakers. What do you see as the necessity or the value of bringing religious voices into those kinds of policy conversations, whether it’s around climate change or I know that faith organizations have been present at the biodiversity summits in recent years as well? What is the hope that they bring into those conversations?

Dr. Iyad Abumoghli: Well, I mean the simplest example is, as Reba mentioned, and everybody was talking about, Laudato Si’. Pope Francis, his leadership, his thinking and his understanding of our relationship with the environment and of course as related to the poor. The leadership is one important aspect. And when leaders, when a priest or an imam or a monk speaks, people say amen. And they listen. And because they speak not only of the power but of the conviction in their religions of the standards that have been there for centuries. So it is the word of God that is being said, and nobody can of course debate that as opposed to bringing a scientist. And immediately people will start, “Oh, where is the evidence? How did you do the data analysis? How did you collect your data?” So they debate scientists. But when you have a leader, a faith leader speaks, they speak of power, they speak of knowledge, they speak of practices. And they bring traditional knowledge because we know that Indigenous people, people of faith have been living in harmony, have been practicing their sustainable relationship with the environment and with earth.

And now the development, economic priorities have taken over and over consumption course and practices of the people. So we need to bring that back to the understanding of the people in the past few years. The first interfaith summit that was held and called for by Pope Francis. And then we followed it up by holding one in Abu Dhabi and one in Baku. I mean dozens of faith leaders came to agree, first of all, on the common understandings of all religions, which brings backgrounds and religious backgrounds together. But second, their commitments and each of the interfaith statements lists what faith organizations and institutions are committing to do, but also it represents their goal for action by the policymakers who control how things move on. So leadership is important and it is very valuable. We have seen programs launched by many religious institutions in the implementation of their own teachings and understanding in living in harmony with nature.

Brian Roewe: Thank you. And I think we might hear about some of those next. Reba, for you with the Laudato Si’ Movement, we mentioned that this weekend will mark the 10th anniversary of the release or the publication of that document. Laudato Si’ Movement formed in early 2015 in anticipation of Laudato Si’, of Pope Francis issuing this major statement. What has the work been like over the past decade for Laudato Si’ Movement, and how would you assess how Catholics have responded to what Pope Francis called for and that in that document?

Reba Elliott: The work has been fast. As Dr. Iyad said, yeah, the response of people of faith, I think across the board to Pope Francis has been really incredible. And we at Laudato Si’ Movement have been so lucky to work alongside partners like Dr. Iyad and so many others who have come together and coalesced into this movement. I can share a few examples. I can share a few stories from the last 10 years. We have a program for training grassroots champions, people in communities who want to do something and they don’t know quite how to get started. We have a training program and we’ve trained 18,000 of those people who we know are active. We know that these people are leading events in their communities because we get photos. So 18,000 people are active in local communities on the ground, and hundreds of thousands more are not going through a certification program, but are, in our case, Catholics who have taken this message into their hearts and wanted to share it with their family and friends.

And as Dr. Iyad said, sharing a message in a faith context is unlike sharing it almost anywhere else, there’s this assumption of trust and among the people who share a community. And an assumption that if my friend in church is asking me to come to a film screening or a prayer service or a tree planting or a petition day for my local legislator to talk about climate and biodiversity, it must be something important. It’s someone that I know. And so to have that kind of grassroots momentum in the last 10 years has been really extraordinary because all of those are stories of people, just ordinary moms, dads, neighbors, teachers, gardeners. Just the people in your neighborhood who are leading this work on the ground, which has been, yeah, just to be touched by this wave of action has been on a personal level, very moving.

But there are also signs of that institutional leadership that Dr. Iyad was talking about. One of the programs that’s been developed in the last 10 years is called the Laudato Si’ Action Platform. It’s a program that’s sponsored by the Vatican and it’s for Catholic institutions like hospitals, universities, schools. That statistic about the number of institutions in civil society that are faith-based is relevant here, I think. It’s a platform for those institutions to become totally sustainable. There’s this phrase that Pope Francis used in Laudato Si’ called integral ecology. And what it means is that everything is connected. We can’t just install solar panels or put those low flow faucets into our sinks. We also need a different economy and different spirituality, different culture, different systems of education. So this platform, the Laudato Si’ Action Platform, helps Catholic institutions develop that integral ecology, install solar panels, but also divest from fossil fuels and also help your communities be more resilient.

To have that sponsored by the Vatican is a big deal. And here in the US, the diocese of Lexington, Kentucky, so the kind of regional unit of the church in Lexington, Kentucky is one of the institutions that has enrolled. And Lexington has also encouraged all of its member parishes to make their own Laudato Si’ plans through the umbrella of this program. So from the Vatican down to the level of the diocese and then down at the level of all the local churches, that kind of institutional leadership is filtering through and people are making real changes. People who are in decision-making positions, positions of power and authority are changing how their institutions are run. I’ll just say one more very quick example. The response in the Philippines has been particularly strong. Pope Francis visited the Philippines in the wake of Typhoon Yolanda, it’s called in the Philippines, the really strong typhoon some 10 years ago and was with people in a mass, he put on a yellow poncho.

There was wind and rain all over the place and Pope Francis was out there with people and giving communion and again, just standing with people where they are. The Philippines has responded very strongly to his call to make action on climate change, more urgent, more ambitious, more real, more fast-moving. The entire Bishops’ conference of the Philippines. So the kind of united body of the church in the Philippines, all the head honchos in the Philippines, they have divested from fossil fuels. They have encouraged all of the Catholic institutions in the Philippines to drop fossil fuels. And they have also turned down donations that come from extractive industries. They don’t accept money that comes from fossil fuels, mining, all that stuff. The average salary in the Philippines is around $200 a month.

And these bishops are making this really courageous and bottom line affecting decision that they’re going to practice what they preach, that they’re going to really act on their values. One of the Filipino bishops whose name is Bishop Gerry Aminasa was in France this past week because French banks are financing fossil fuel projects in the global south. It is colonial extractivism in the most plain and obvious way. And Bishop Aminasa was there for the general meetings of those banks to look bank executives in the eye and say, “Your fossil fuel project is in my country. France, I’m here to deliver a message of moral leadership to you directly to call on you as someone from the Global South speaking to the Global North. Please make different choices.” And yeah, I think that those, again, that’s one of the stories of someone who’s just taken this into his heart and acted on it. And there are just thousands and thousands and millions of stories like that over the last 10 years.

Brian Roewe: Thank you. Thank you. That was a nice summary. I know there’s a lot that’s happened just from our own reporting in the past decade. So here’s a question for both of you. Covering Climate Now just launched the 89 Percent Project, which is a global media collaboration aimed at highlighting the fact that the vast majority of people in the world care about climate change and want their governments to do something about it. But the fact is that’s not widely known or discussed, so that helps explain why the 89% don’t know they are a part of a global majority. A similar phenomenon we can see playing out in religion. A recent study surveyed 1600 mostly Christian leaders, and nearly 90 said they believed human-caused climate change, or excuse me, nearly 90% of them of whom believe in human-caused climate change.

Yet half of them said they never discuss it and their sermons or teachings and only 25% or a quarter have mentioned it once or twice. Researchers also surveyed Christian churchgoers asking them what percentage of religious leaders in the US that they thought believed in human-caused climate change, and they underestimated it by 39 to 45%. So I’m curious, both of you, what are your reactions to those findings? Does that ring true to your experiences that faith leaders might affirm the scientific consensus on climate change but aren’t talking about it? And how are your organizations working to encourage faith leaders, especially priests and imams, to talk about congregation within their faith communities? Dr, Iyad, do you want to start first?

Dr. Iyad Abumoghli: Sure. Well, unfortunately it is true what you have mentioned and what I call it, I call it religious illiteracy when it is concerning the environment. We understand our religions and we understand how to do our rituals and how to pray to God and how to do pilgrimage and how to give charity, but we do not understand how to live in harmony with nature according to our religions. And I’m generalizing because this is, as you mentioned, surveys prove that not too many people understand. And indeed it is partly because we do not understand. Nobody has helped in explaining the relationships, but also because the scientists, the language of the scientists is not clear. When you talk about climate change and increasing the world temperature, what does that make any difference for somebody who’s living in the desert, for example, with 40, 50 degrees centigrade, one or two degrees wouldn’t make a difference if it is getting colder in other areas.

So that needs to be explained in plain language to the people to understand that it is not an abstract science that we are talking about. It is about impacting the society, impacting the farming, impacting the water resources that we get, hardly in many cases; it is about agricultural practices, the plants that they produce and so on that this will impact their livelihood. So when we try to explain that, then probably you will expect, as we have been seeing for the past few years, that the attention has been increased by regular people wanting to understand more. And this is why, as I mentioned before, UNEP has come up with so many publications. Currently, we have more than 40 publications on this specific issues, all the contemporary environmental issues related to religions. And we have taken at least 15 religions and explained those issues from their own perspective.

So we are not talking about only Christianity or Islam, we’re talking about 15 more religions and how they relate to the environment. But also it is important that you provide to those who are underprivileged. So not only we published printed material, but we have also issued online courses, free courses that are available for anybody. There are nine courses out there with the plain language, explains everything and makes the scientific knowledge in a very plain language that could be understood by everybody. So we have been doing capacity building, workshops, webinars, every opportunity that avails itself, we are utilizing it to bring that to the knowledge of everybody. The most important part is that we speak to the leaders, and I mean not only at the level of the Pope, but going down to a priest in a very local village. This is where something like Laudato Si’ or Al-Mizan can be of benefit. Those documents will enrich the knowledge of those local leaders who have access to local communities that can make that understanding available to their followers.

Brian Roewe: Thank you. Reba, do you have thoughts as well?

Reba Elliott: Sure, yeah. I’m totally appreciative of the work that Dr. Iyad and his team have done to collate all that study on how different religions have approached the environment. Yeah, I think that there is something in the fact that so many of us people of faith and secular people are aware of the climate crisis, and yet we think that others are not. There’s that strange gap, that strange disconnect that we don’t know that others think the same way that we do, have the same awareness that we do. I think that that has a little bit maybe to do here in the US in particular with this perception of polarization around climate change.

There is some truth to the issue of climate being polarized, but I think that the studies that look at polarization around climate are limited because they miss this really essential fact, which is that there is still within the US a big group of people who are centrist and open to different opinions and perspectives. And I think that sometimes within communities of faith, we have a reticence to discuss issues that we’re worried might be controversial or might start a fight or might make people feel uncomfortable. But the good news is that climate change is not one of those issues. The good news is that the vast majority of people of faith are aware of the climate crisis, aware that it’s caused by human beings and aware of the teachings of our faith that guide us to honor our creator by caring for creation and each other. And if we were more comfortable talking openly about that, we would find that we actually have a lot of friends who think the same way we do.

Brian Roewe: Thank you. I want to jump in. Dr. Iyad mentioned Al-Mizan. So question for you on that topic since you brought it up the last year. This was a document that Muslim scholars issued, Al-Mizan, which Faith Earth Coalition helped coordinate. Can you describe a little bit what the document is, what Al-Mizan says, and what are some of its main takeaways and also what has been the reception in the past year?

Dr. Iyad Abumoghli: Well, thank you for asking this question and I’ll be quick in my answer because I believe we need to listen to the audience. Well, Al-Mizan is, I want to put it simply, the Islamic version of Laudato Si’. Laudato Si’ is based on the Bible. The teachings of Christianity and Al-Mizan is based on the teachings of Al-Quran and the practices of Prophet Muhammad. Peace be upon him. It is called a covenant for the earth. So what we extracted actually is the relationship between humans and the creation and the environment. And in Al-Mizan there are more than 50 principles extracted from Al-Quran and the Prophet practices talking about our relationship with the environment. For example, we refer to Al-Mizan itself, which means balance in English. And God has clearly mentioned in the Quran that he has created everything in balance. So he created pairs of everything.

He created the moon at night, the sun in the morning, stars, he created trees and even looked at the body of a human being. Everything is in balance. The heart pumps the blood, blood goes and carries the nutrients. So everything was created in balance, but also God says in the Quran, that humans have been known to breach that balance because of their greed. So we talk about the greed of the people, and this is, I think, is agreed by all other religions that greed has taken us where we are now because we want to consume more. We want to abuse the stewardship responsibility as mentioned in the Al-Mizan is called Khalifa. Khalifa is a steward or a person who’s responsible for the creation of God. God and Al-Mizan talk about the oneness, our interconnectedness with the creation. So we are all in one, which is the oneness of God as well.

So the Al-Mizan describes the nature of current crisis. The good thing is that it came seven years after Laudato Si’. So many things have happened already after Laudato Si’ was launched. So it was captured by Al-Mizan, for example, fossil fuel, for example, proliferation treaties that are being discussed and all the discussions at the COPs, it was captured in Al-Mizan. And then Al-Mizan relates all of these contemporary issues from the perspective of the Quran. Currently, it is available in eight languages. There are three more languages coming up in the next couple of months. We are nationalizing Al-Mizan. So Al-Mizan is a global document. It was yes, written by scholars, but it was adopted by the highest Islamic authorities like Al-Azhar, like the council Muslim of Elders and so on. And we have consulted more than 350 Islamic organizations worldwide. So it became an Islamic document. Now we are nationalizing it.

We have launched a national committee of Al-Mizan in Jordan. And in Jordan they launched the first national Al-Mizan park that uses the ecosystem restoration principles in Al-Quran for the management of ecosystems in that park. We have launched the Zanzibar Ecotourism based on Al-Mizan and the teachings there. And we have now been working with Pakistan and Malaysia to launch their national strategies based on Al-Mizan for religious-based advocacy and moral responsibility. The most important part, as Reba mentioned, is the moral authority of religions towards the environment. It is not only science and technology and policies, but it is the moral value-based authority that we as humans have over the environment and how we live in balance and in harmony with nature.

Brian Roewe: Thank you for that. Thank you both. We have had some audience questions coming in, so I’d like to turn to some of those. First one was from Diara Townes. She’s an investigative journalist with Sunlight Research Center and she wants to know, her question is, faith organizations, how do they overcome the challenge or questions of authenticity, especially the role that faith communities have had, especially here in the United States related to the doctrine of discovery or slavery. So how is that something that faith communities can talk about stewardship in the environment today in a way that is convincing to people that might have questions or concerns about what the role of faith communities in past atrocities?

Reba Elliott: Yeah, that’s a great question and thank you. I’m sorry if the name was Diara, I couldn’t quite catch it, but thank you for asking the question. Yeah, that’s a really great question. And I think that it would be disingenuous to not acknowledge that faiths and in particular Christianity and in particular Catholicism have had in subjugating peoples and the rest of creation animals, plants, lands, waters that have been abused and used and entire communities. Yeah, I mean communities in the sense of individual places of people living and communities in the sense of peoples in themselves that have been similarly abused and mistreated in the name of religion. And it’s difficult to square that history with a worldview that says that every living creature is to be treasured and that all people have equal dignity and worth. There’s a history there that doesn’t quite hold with some of the other things that religions like Christianity teach us.

And there’s no way to make those things come together. There’s no way to say that they’re not complete and polar opposites. And I don’t want to justify or apologize for anything that has been done in the past or is happening now or maybe done in the future. I don’t think that’s possible. I will briefly say that the Catholic Church has tried to, in some ways, not in ways, but in some ways it has tried to be more mindful of that role that it has had and in some ways still has. So I can give a couple of quick examples. One is that a few years ago there was a global gathering of leaders of the church. It’s called a synod, and this synod was Synod on the Amazon and Pope Francis organized this global event in order to help the church reckon with its past in the Amazon and to better understand how everyone, every Catholic in the world can now learn from and be guided by the Amazon church today. Laudato Si’ Movement was doing some work around this synod.

And as part of this, we were reaching out to traditional Indigenous communities there. And some of the people that we talked to said, “Look, we can’t collaborate with you until we check with communities on the ground to see whether they’re comfortable working, working with a Catholic organization.” And all of the communities that were approached said that they wanted to work with Catholics because Catholics in the Amazon today are seen as protectors and champions of traditional Indigenous communities. I’m sharing this to say that there’s no way to square up some of what has been done and what continues to be done in subjugating and dehumanizing people and in subjugating and exploiting the natural environment. There’s no way to square that up with the belief that we should respect and care for each other. And at the same time to say that, and others might think differently, but my impression is that in some ways the Catholic Church is trying to be more conscientious and to play a more coherent role now. But yeah, thank you again for that question.

Brian Roewe: I think we might have time to squeeze in one last question. So this comes from Cynthia Astle with United Methodist Insight, she said, or she’s wanting to know what guidance you could provide on how making fossil fuel divestment least harmful to those who have relied on its financial support in the past. She mentioned that there was a regional United Methodist church unit in California who recently agreed to divest completely from fossil fuel holdings. But this is an issue that gets a lot of pushback within the United Methodist Church, and I can speak from reporting, it gets pushback in other churches as well. So what guidance might you offer in those situations?

Dr. Iyad Abumoghli: Well, if I may respond to this, it doesn’t have to be this way or that way. Of course divestment is something that has been adopted. More than 55 churches at the global level have committed to divestment. In 2020, there was an agreement to divest $11 billion investment in fossil fuel. And there are alternatives. So if investment in fossil fuel generates resources that goes back to the community, which in most cases I doubt. It doesn’t go back to the communities probably at a level of charity rather than investing back into the society, there are other alternatives. Running now a car or running a house on a solar-powered system is much cheaper than running an industry on fossil fuel. There are of course global agreements that manages the carbon trading.

If you base your economy, for example, on fossil fuels, you have to compensate for that by paying your carbon tax to other countries or to the people who are being impacted by your investment in fossil fuel. So there are many examples. On the individual level, we have launched what we call the Moral Imperative Initiative with the World Council of Churches and the Muslim Council of Elders. And this works with the local bank. So anybody can go to the bank and question the CEO, where does my money go when I put it and save it in your bank? How are you treating it? How are you using it? Are you investing in fossil fuel? Are you investing in environmentally harmful investments? So this movement has started and we have dozens and dozens of people who have done, and they have even changed their banking system because they do not uphold the sustainability principles.

So there are always other alternatives. And this is why we’re saying knowledge is important. We are the most knowledgeable generation ever existed on earth and we have everything under our fingertips. It needs to be scaled up, all these innovations here and there. They need to be the mainstream rather than an innovation here and there. So when we start applying, there are global agreements, but when it translates to national legislation and regulations, of course sustainability will be the norm. And it will provide the answers and alternatives to all these issues that we fear that if we don’t invest in oil, then where are we going to get our resources from? So I believe there are alternatives.

Brian Roewe: Thank you. Thank you. And that’s definitely an aspect that’s right for more reporting is the relationship between fossil fuels and investments with faith communities. So we’re getting close to the end here. So I’d want to give both of you just one last minute for any closing remarks that you might have. Reba, do you want to start?

Reba Elliott: Sure. Well first just to say thanks again, Brian. Thanks to Covering Climate Now. Thanks to Dr. Iyad for the opportunity to speak alongside him. This is such a pleasure and I’m really grateful for all of y’all who have turned up and listened for this conversation and for sharing our questions. I wanted to mention quickly that on the next Friday there is an event for Laudato Si’ week. So this is the celebration of the 10th anniversary of Laudato Si’. There is an event at 15:00 Rome Times, that’s nine AM on the US East Coast, six AM US West Coast. That event will highlight stories from the ground all around the world, give a sense of that united action and momentum, as well as touching on some of the big picture progress that’s been made. So would love to have anybody there who would like to come. We’d be so honored to share our stories with you. And yeah, hope to see you there and thanks again for everyone for the event today.

Dr. Iyad Abumoghli: And from my side, of course, I invite you to celebrate the World Environment Day that is coming up on the 5th of June. And the main theme for this year is beating pollution. So try in your congregations and discussions to bring up the issue of pollution because it is causing at least six million deaths of children every single year and many, many more with adults. Another thing that I wanted to mention is that please refer to our website. We have plenty of resources. We have guidelines on sustainable living by faith actors. We have guidelines on greenhouses of worship. We have guidelines on how to protect biodiversity by faith organizations. We have guidelines on how to plant trees that are called God’s trees. So there’s plenty of resources. Education and knowledge is the key towards living in harmony with nature. And we have the knowledge out there. It just needs to be captured and practiced. Thank you.

Brian Roewe: Well, thank you Dr. Iyad. Excuse me. Thank you, Reba, as well for your time and the conversation today. I am going to pass it back to David now.

David Dickson: Thank you all again. And once again, I want to personally thank Brian as well as these wonderful panelists for joining us. I think it’s been incredibly insightful and hope it has been for you all as well. When this webinar ends, you’re going to be asked to respond to a survey. We ask you to complete this. It’s very valuable feedback that helps us plan further programming from us over at Covering Climate Now. It should only take a minute. I also encourage you to sign up for our newsletters at Covering Climate Now so you can further stay informed in the climate story globally and in our communities.

I also hope you’ll join us for another webinar we have coming up here at Covering Climate Now tomorrow, May 21st at noon Eastern Standard Time in the US in which we’re going to be highlighting how climate change is fueling changes to the extreme weather that we’re going to be seeing this summer from supercharging Hurricanes to intensifying deadly heat. Check out the link in the chat that my colleague Theresa just put for more information and to RSVP. And otherwise stay in touch and thank you all once again for joining us.