More voters face national elections this year than ever before. Last year was the hottest in recorded history — and scientists warn that oil, gas, and coal burning must be rapidly phased out if we are to preserve a livable planet. How can reporters — both on and off the campaign trail — connect those facts?

Panelists

- Margaret Sullivan, Executive Director of Columbia’s Newmark Center and columnist for the Guardian

- Ben Tracy, CBS News’ Senior National & Environmental Correspondent

Key Takeaways

- Focus on consequences, avoid false equivalency in elections coverage

Sullivan critiqued elections coverage so far this cycle for its usual heavy focus on the horse race, and urged journalists to instead focus on the consequences of different election outcomes. She warned against false equivalency, where, for example, US media portrays both major party candidates as equally viable, even when their positions on crucial issues like democracy are fundamentally different. News organizations engage in false equivalency for fear of appearing partisan, Sullivan said. “I get that. But the result of that is to equate things that shouldn’t be equated.” Trump is “anti-democracy,” she said, and “… will take down some of the guardrails that were there during his first administration.” Biden, on the other hand, is a vocally “pro-democracy candidate.” She argued that comparing two candidates as equals “on such an important issue” misrepresents reality. Sullivan urged newsrooms to be hyper-aware of this tendency.

- Covering climate politics requires nuance

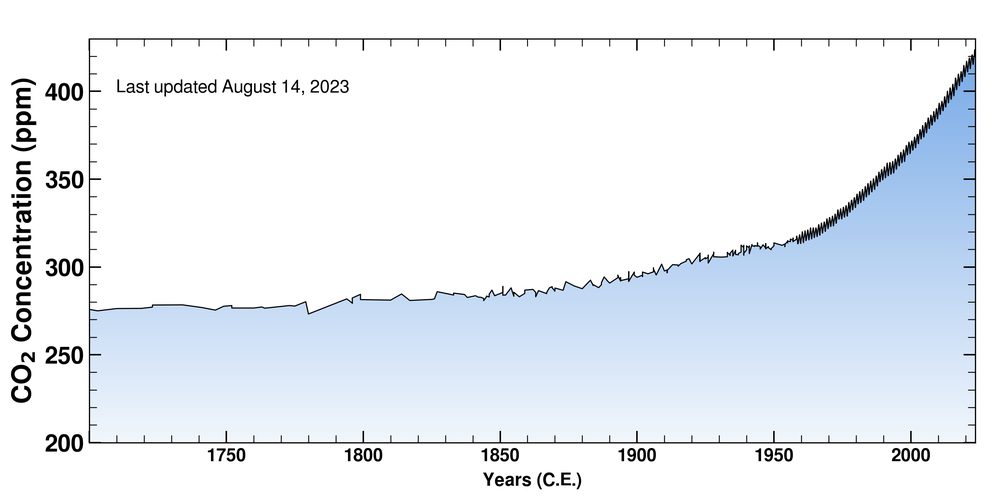

In this year’s elections, “climate is very much on the ballot,” Tracy said. He plans to shift his reporting to focus on this. “It’s not hard to cover it from a nonpartisan lens, but it’s hard for your coverage to be seen as nonpartisan in the [polarized] environment that we all work in right now.” Highlighting the genuine differences between Biden and Trump’s approach to climate policy is essential. Educating audiences about the urgency of the situation is paramount as the window for effective climate action quickly narrows, Tracy said. “We don’t have four years to hit the pause button on climate policy and our emissions cuts,” he said. The science-backed deadlines are to halve carbon emissions by 2030 and reach net-zero by 2050, which point to the gravity of the issue. Audiences also need to be made aware of the real global repercussions if the US were to backtrack again on its climate commitments.

- Ensure your reporting, interview selection, and finished piece reflect the science

When he started on the beat, Tracy said, covering some climate issues felt like taking a side. But he quickly realized that the overwhelming scientific consensus meant “you’re really just reporting facts like you are for other stories.” Tracy reflected on some audience pushback he’s gotten about the reality of climate change. To combat this, “I always, in pieces, really go out of my way to start a sentence with, scientists say, or the science shows this. So it’s not my opinion, it’s not me just listening to a politician who has a thought on this.” Since climate science is as settled as gravity, Pope urged journalists to refrain from asking candidates whether they believe in climate change or not, but instead to ask candidates what they plan on doing about climate change.

- Report on how the US elections could impact the Global South’s climate future

How will the results of the US national elections reverberate in the Global South? Report on the concrete impacts of each presidential candidate’s climate policies, Sullivan suggested, including how their plans would affect local efforts and exacerbate existing challenges. “I’d read that story,” she said. Tracy added that this was fundamentally about the stakes of the election, and that a rollback of US climate policy changes could have significant consequences for vulnerable countries disproportionately affected by climate change. If there were a change in US leadership, Tracy said, it’d be important to explore whether countries would remain committed to international agreements despite US inaction, or whether they’d say, “If the US isn’t playing ball, then let’s all just do our own thing.”

Resources

Climate on the Ballot, CCNow’s weekly US elections newsletter, helps journalists integrate climate into their coverage of elections at every level — local, state, and national. Sign up.

“The planet is on a fast track to destruction. The media must cover this like it’s the only story that matters,” a 2018 Washington Post column by Margaret Sullivan

Ghosting the News: Local Journalism and the Crisis of American Democracy, Margaret Sullivan’s 2020 book about how the hollowing out of local news threatens democracy

“EV battery manufacturing energizes southern communities in ‘Battery Belt,’ a CBS News segment by Ben Tracy and Analisa Novak

Transcript

Mark Hertsgaard: Hello and welcome to another talking shop with Covering Climate Now. I’m Mark Hertsgaard, the Executive Director of Covering Climate Now and the Environment Correspondent for the Nation Magazine. Today’s subject, climate on the ballot 2024.

But first, for those who don’t know, Covering Climate Now is a global collaboration of more than 500 news organizations that reach a total audience of multiple billions of people. We’re organized by journalists for journalists to help one another do more and better coverage of the defining story of our time. It costs nothing to join Covering Climate Now, and there’s no editorial line, except or respect for science. You can go to our website, CoveringClimateNow.org, and find a list of our partners. You can sign up for our weekly newsletters, the Climate Beat and Climate on the Ballot. Check out our resources and apply to join Covering Climate Now.

Now, as you doubtless know, there are scores of elections taking place around the world in 2024, at the local and national levels. These elections will largely decide humanity’s climate future, because they’re going to determine what governments are in power and out of power over the next five years, when the global emissions curve must bend downward towards zero if we are to avoid climate breakdown on this planet. So, it’s hard to think of a more important or a more dramatic story. Nevertheless, most news outlets are ignoring the climate connection in the 2024 elections coverage so far.

Today’s talk and shop will explore the reasons behind that silence, and more importantly, what might be done about it. Moderating the discussion will be my esteemed Co-Founder of Covering Climate Now, Kyle Pope. Kyle, take it away.

Kyle Pope: Thank you, Mark. And welcome, everybody and thank you for being here. For those of you on the West Coast, hope you’re enjoying our brief taste of winter, first big snow in two years. We’re happy to have it.

Just to build a second on what Mark said, our job today in this discussion is really twofold. The first is to acknowledge the fact that despite everything we know, climate issues still aren’t getting the kind of attention the story deserves. Fundamentally, it means that on this issue, journalism isn’t doing its job. And what we want to think about today is, why is that? What is it about the way campaigns are organized, the way politics’ desks cover issues that make this so hard? Why is climate not one of the dominant themes of this election season?

And this isn’t a rhetorical question. It’s something we really need to know the answer to because that will help get us to solutions. And that’s what we’re going to talk about today. What does a good climate coverage look like in a political season like this one? How do we engage our audience in a story we know they’re interested in? The data always shows that. People want to know more climate news. How do we give them that in a way that it resonates?

So, we have two of the best people on earth to talk to about this. And I’m going to turn to them in just a minute. But before I do, let me just underline something that Mark said about the moment that we’re in, which is, we are on this planet quite literally at a tipping point. The decisions made by the people we vote into office this year, particularly in the U.S., are going to profoundly affect our climate future. This isn’t a matter of, let’s make some progress down the road or let’s get the ball rolling. We’re past that point. We can talk in a way that we, as journalists, understand. The deadline is here. There’s no more time left. So, when we talk about the need to cover climate and about the need to focus our political candidates to address it, we need to do this with urgency. And that’s why we need to address these issues now, today because the political season to the upon us.

So I’m going to introduce our guest in just a second. We’re going to talk for about half an hour. After that, you’ll have an opportunity to ask questions. Use the Q&A function on Zoom to ask questions, and we’ll get to as many of those as we can. If you want to tweet, use #ccnow at @coveringclimate.

So, let me give a warm welcome to our panelists. Margaret Sullivan is a weekly columnist for The Guardian and the new Executive Director for the Craig Newmark Center for Journalism Ethics and Security at Columbia Journalism School, which is my old stomping ground. No one, no one writes more thoughtfully and forcefully about the news business than Margaret. She’s also written a terrific book about the crisis facing local news called, Ghosting The News: Local Journalism and the Crisis of American Democracy. We’ll talk in a minute about the link between local news and climate coverage.

And finally, let me just say that on climate, Margaret has been ringing this bell for years. When Mark and I started Covering Climate Now in the spring of 2019, we were often getting blank stares from newsrooms, as we implored them to please do more climate coverage. And it was a huge boon to us that we were able to point to a piece that Margaret had written that fall in the Washington Post that was headlined, The planet is on a fast path to destruction. The media must cover this like it’s the only story that matters. And we’ve used that mantra over and over again. So thank you for that, Margaret.

Ben Tracy, is CBS News and Senior National and Environmental Correspondent based in Los Angeles. He reports for all CBS News platforms including the CBS Evening News with Norah O’Donnell, CBS Mornings, and CBS Sunday Morning. Before covering climate, Ben was a White House correspondent for CBS News and covered the second half of the Trump administration. His decision to leave the White House and devote his career to the climate story is inspiring. And his role in CBS’s climate coverage is critical, given that he understands how politics coverage works and how to make climate part of that story.

It’s also a great opportunity to talk to Ben about the unique demands posed by a visual medium like television when you’re covering a story like climate, given the constraints on time and the need to tell the story in pictures. So, I’m interested to get into that. Before moving to Washington, Ben was based in Beijing where he covered Asia for CBS News.

So, let’s start with Margaret. Margaret, you’ve written forcefully and often actually, about what you see as the flaws in how the U.S. press tends to cover politics, especially presidential politics and especially in this country. You’ve talked about the problems of the horse race, the reliance on polling, the false equivalencies that still exist between two candidates. Frankly, a lot of us simply can’t believe that we’re facing a rerun of 2020 and that Trump is once again on the ballot.

Let’s put aside just for a second, we’ll talk about climate in a bit. But I’m just curious in general, when you look at the shape of the overall coverage, how do you assess it so far? What do you see that the political press has learned from 2016 and 2020? And what do you dismay that they seem to be doing again?

Margaret Sullivan: Well, thank you very much, Kyle, and thanks to you and Mark for forming this organization and for doing all you do to make sure that our planet somehow makes it through the next however many years. It’s really important, and media’s role in it is extremely important too. So, thanks for having me and great to be here with Ben who’s a practitioner, unlike myself at this point. I’m sort of on the… just watching, sometimes with dismay.

So as I look at politics coverage, particularly of the presidential election in the United States, I see some good stuff. And I see a lot of things that I wish I could change. So, what are the things that I wish I could change? I think we are still not focused enough, and I say we, I mean the media writ large, and I’m talking about the mainstream media here. I’m really not talking about the right wing media. That’s kind of a separate story. But I think we’re still, not a little, we’re still much too focused on who’s winning the horse race. We’re not focused enough on what the consequences of the election will be. I see some stories like that and it’s great to see, but if you were to do a content analysis and compare the two, I’m pretty sure that the horse race coverage would come out ahead, by far.

In addition, I think there’s still a tendency to want to equate the two major party candidates, even though they are extremely different. And there’s a reason for that, at least I think there’s a reason for it, which is that I think editors and publishers and news organizations and their bosses really feel strongly that they don’t want to be seen in any way as partisan. And that’s fine. That’s good and fine. I get that. But the result of that is to equate things that shouldn’t be equated.

So to make it fairly clear, if the election ends up being, as it seems like it’s going to be, a Trump versus Biden redo, we’re going to have a candidate who is pretty much anti-democracy in a lot of ways. We know that Trump and his allies are planning to do a lot of stuff if he’s elected again, that will take down some of the guardrails that were there during his first administration.

And Biden, you can have all kinds of problems with him. You may not agree with his stances, all of that, but I think it’s pretty clear that he is a fairly traditional and therefore pro-democracy candidate. So to kind of make them equal on such an important issue, is what we like to call false equivalency. And it’s something we should be hyper aware of.

Kyle Pope: We all, who watched the media, wrote about false equivalencies after the emails in 2016. We wrote about it again in 2020. I sort of can’t believe we’re writing about this again. What is the resistance? I mean, why is there not more of an acknowledgement? What is it that’s baked in here that makes people repeat themselves over and over again on this problem?

Margaret Sullivan: I mean, it’s a little hard to understand honestly, because there’s been so much criticism and even acknowledgement of what went wrong during the 2016 campaign and what went wrong during the coverage of Trump. I know I’ve written about it an awful lot, and I think there’s awareness of it. But somehow you’re right to use the word, baked in. I think that there’s sort of this tradition of, this is how we do it.

And I think there are two things going on, basically. One is, and I just mentioned it, not wanting to seem partisan, so you equalize the unequal. And the other piece of it, and this is hard to quantify, but I think it’s true, is that Trump is great copy. He called himself, back before he was in politics, a ratings machine. And he does attract attention, sometimes for very damaging and troublesome reasons. But the whole idea of covering Trump and his candidacy and earlier, his administration, was this kind of rollercoaster ride that did generate a lot of interest. Some of it was sort of fear-based. And I think there’s a tendency, there’s a deep desire to keep our audiences coming back, and to do the stories that are sexy and to do the stories that are going to get ratings. And Trump does do that.

Kyle Pope: So let me ask you about climate, Margaret. It seems to me that climate belongs among a long list of important deep issues that should be covered in a campaign like this, but often aren’t, housing, healthcare, inequality. Talk to me about why these sort of big totemic issues tend to present such a challenge for people.

I mean, Mark referred to this earlier when he was talking about the climate story. To us, the way we see it at Covering Climate Now, this is a great story. There’s big drama, there’s huge stakes, there are real villains, and yet people don’t see it like that. Why do you think newsrooms have such a hard time with these kind of slow moving huge stories?

Margaret Sullivan: Well, I think you put your finger on it when you said slow moving and huge. It’s often there’s not a breaking… Unless there’s a big report that comes out that is scary and gets attention, there’s not a lot of breaking news in it. There’s not a lot of sort of the normal developments that are the meat and potatoes of coverage. So, you have to be enterprising. And some journalists are enterprising and that’s great. But it doesn’t sort of present itself as a story in the same way, for example, that immigration does.

And similarly, you have the public with a story like immigration, which is big and sweeping and substantial and all that, you have extremely different points of view on it. You’ve got conflict, which we love. And you’ve got a candidate in Trump who has based a lot of his appeal on issues related to immigration. And so, there’s a lot there to sink your teeth into and a lot that feels familiar. I think climate is really different from that, but that’s a cop out and I don’t think we should be copping out. In fact, as you and Mark have said, it’s a really interesting story and it couldn’t be a more compelling story. We also know that it’s of tremendous interest to younger readers and audiences, and we should care. We do care and should care about younger readers and audiences. So there’s a lot there that should be compelling, but I think that it’s that slow moving this, it’s the fact that it can be gloomy and that it’s not an easy story to cover in a lot of ways is part of the problem.

Kyle Pope: You mentioned migration. One of the things that we think is that every story eventually has a climate connection and part of telling the climate story is drawing that out of things like immigration, things like housing, obviously weather, but infrastructure, everything. Ben, let me ask you, I mentioned that in the intro, this decision that you made to leave the White House beat, which is the place that most people in network TV want to end up and move over to climate. Can you talk to me about your decision making behind that? What led you to that decision and how you were seeing, maybe even reflect back on what some of Margaret was saying about the way politics is covered?

Ben Tracy: Sure. Yeah. I had covered the last two years of the Trump administration and Margaret mentioned the rollercoaster. It was definitely a roller coaster two years. It was two impeachments, insurrection, summer of civil unrest in the country. It was a bonkers time, and I feel like in dog years, it was maybe 10 years of covering the White House.

Kyle Pope: I think all of us in the country felt the same way.

Ben Tracy: As a journalist, it was fascinating. It was an amazing place to be and to see that all up close, and I didn’t even mention COVID in there, which obviously was the predominant issue happening at the time.

But for me, just personally when the election came up, I just felt like that was enough for me and I didn’t see myself being a political journalist long term. And I think we have people who are better suited to do that day in and day out. And I was interested in climate and environmental coverage just as something that I was reading about and just trying to educate myself on and went to the bosses and said, “I think we could do more on this topic. We’re not covering this as a real beat.”

And to their credit, they took me up on it right away. It wasn’t hard to convince them. Maybe that was just, they were like, sweet, you want off the White House speed? I’m sure we can find somebody else to do that, and here’s something else you’re going to do. And to be honest, in the beginning, I think everyone thought it would be like, go cover the EPA and the Department of Energy, which we all know is a ticket to never being on network television. So we went out and said, we need to take people places. We need to show people solutions to this crisis and tell the problem through the solution. And that’s what we’ve been doing for three years.

So I have to admit, bringing this back to politics, I’m a little conflicted about the idea of knowing that we’re going to have to dive back into politics in some fashion this year because we’ve really gone out of our way to depoliticize our coverage, to not make it about this is what the Republicans support and this is what the Democrats support. And really just try to educate people on the science and what’s being done to try to address that and the timeline that we have to address that.

Now, I’m not naive. I know that politics is a huge part of this, and climate is very much on the ballot in this election, and the differences between the two main candidates are pretty stark. So we’re going to have to jump back into this, but it is hard because it’s a partisan issue and it’s hard to cover it. It’s not hard to cover it from a nonpartisan lens, but it’s hard for your coverage to be seen as nonpartisan in the environment that we all work in right now.

Kyle Pope: So talk to me a little bit more about that, about not covering it as a politics issue, because as you say, it is. It’s in the air, people are fighting about it, the candidates are talking about it, voters are talking about it. How do you separate those two things?

Ben Tracy: Well, we don’t shy away from politics when the politics are really germane to what we’re covering. So for instance, I did a piece a couple of months ago about the build out of battery manufacturing down in the south. In particular, what people are calling the battery belt where they’re building both battery cells plus recycling and all sorts of things to support the EV market. And we made a real point in the story of saying that the investments are going to these states where for the most part, Republican lawmakers opposed the legislation that created all the jobs that a lot of them are now touting and taking credit for because it did seem very important to that story to talk about that. But if we’re just doing a story about carbon capture or some other climate related story, we haven’t gone out of our way to try to bring politics into that.

And some of that I think is the thought of you want people to listen to what you’re talking about and not just see it through partisan lens, which we know in this country right now, you go to your team right away and say, well, my team thinks this about that, so I’m not going to hear you out. I don’t think we can do that all the time. And I don’t think it’s appropriate to do that all the time. But as we’ve been trying to focus mostly on solutions and educating folks in the science, I think it’s a somewhat effective approach. But we’re in a different place now. And now there’s a real choice that’s going to be made about what our climate policy is in this country for the next four years.

And I think you set it up really nicely at the beginning that one of the things I’ve been thinking about a lot when we inevitably do these stories in the coming months is not just former President Trump says, “Drill, drill, drill. And President Biden says, “Well, we can drill a little bit here, but not as much as he wants to.” There’s a larger context that I think we need to make sure viewers and readers are aware of, and that’s this timeline issue of we don’t have four years to hit the pause button on climate policy and our emissions cuts. If we believe the science and the science tells us that by the end of this decade we should be cutting emissions in half and down to net-zero by 2050, you don’t have four years to lose.

And also I think there’s real repercussions if the US were to fundamentally backtrack on climate policy, how do other countries respond and is there a spiral to that? We’ve seen how hard it is even at cop, the most recent one where countries who have leaders who are generally on board with this sort of thing to get agreement for aggressive action. And if you had a country like the US just say, okay, we’re not playing anymore, I do wonder what that does geopolitically.

Kyle Pope: So I think this, you alluded to this and Margaret did too. So maybe it’s a good time to talk about this notion of a resistance in the news business to more aggressive climate coverage because it feels like activism or it feels like partisan. And I’m just curious, first from you, Ben, and I can follow up with Margaret, do you feel that concern? Well, first among your viewers, have you had that pushback or the work that you’ve been doing? For example, when you did the battery belt story, which by the way, we’ll put a link in the chat, it was fantastic, if those of you haven’t seen it, did you get that there? And then also do you get that within the newsroom? People are like, oh, you got to be careful?

Ben Tracy: To answer your second question first, no. I have to say I’m really grateful for the support CBS has given to our climate coverage. For something that we just started with me and a producer, they’re now building out a real infrastructure and the network around our climate coverage, and they’ve been very supportive. And these pieces, especially when you’re doing television and you’re trying to take people places, these stories are not cheap. So it’s also a financial investment that the network has made. So I don’t have complaints from that side.

It’s always hard in television to know what the viewers are thinking. Really, all I see sometimes are the responses on Instagram or Twitter, and that is a fundamentally flawed way of trying to interpret what your audience thinks. But you can imagine what they are. We did a social media post a couple weeks ago about why even though it’s freezing out, we’re still going through… Global warming still exists even though it’s freezing in the country and some of the responses, it’s just amazing what people say.

So certainly there is some pushback from some folks in the audience who just aren’t predisposed to believe what you’re saying. I always in pieces really go out of my way to start a sentence with scientists say, or the science shows this. So it’s not my opinion, it’s not me just listening to a politician who has a thought on this, but you’re not going to win over everyone.

So I do think that is a challenge. It’s thankfully, me as a journalist at CBS news, it has not been a challenge in terms of I don’t think we’re doing less coverage because of that thought. I do think some of the things you mentioned earlier about this seeming lack of urgency about the problem and this being more of a slow moving natural disaster, I’m sure everyone on this Zoom would probably think differently about that, but that is the way this is perceived when you compare it to something like immigration or the wars in Ukraine and Gaza, which have daily developments.

Kyle Pope: I’m so glad… I mean, thank you for that. And also thank you for mentioning that you start your sentences with science says. It’s such a good reminder and reminder to all of us that the scientific consensus on climate at this point is basically what it is for gravity. There isn’t a debate, and that’s why we always implore journalists when interviewing candidates, don’t ask them whether they believe in climate change or not, because it’s not really a legitimate question. It’s more about what are they going to do about it.

Margaret, I want to pick a little bit more on this issue of activism and reluctance. I’m interested in your view on this particularly because you’ve written a lot about democracy and how democracy is on the ballot this year and how journalists need to engage with that fact and not shy away from it, to lean into that fact that if you care about democracy, which journalists, it’s okay for them to care about that, they need to defend it and they need to see it as something that’s not outside the norms of journalism. And I’m wondering whether you can draw a line between that view and why we can’t think of climate in the same way.

Margaret Sullivan: Yeah. Sometimes when I talk about this or am asked about it or thinking about it, I start with what would every journalist and probably most members of the public think is perfectly okay for journalists to care about? And should, for example, they care about freedom of the press, press rights? I think it’s logical, yes, we care about that. Most reasonable people think that that’s okay. And what about civil rights issues? And that has come up in newsrooms. Can you protest? Can you sign a letter? Can you do all these things? And there’s a lot of arguments. Can you tweet about it?

So democracy is on that spectrum, I think, but I think that climate change, because it affects everyone on the planet and because the science is clear on it, I don’t think it’s out of whack for journalists to… Again, I think we do our work through the journalism. Ideally, we don’t do it by traditional activism, marches and all that sort of thing. I think we do our work through our reporting and through the way stories are framed and the way we choose what’s an investigative project we want to do. So I’m not talking about marching in the streets, I’m talking about what kind of journalism we do, and I don’t know, I would like to hear the argument against that. I don’t know what it would be, but I do agree that there’s a resistance to it, just a hard to quantify, hard to even express maybe that’s not in keeping with our role as objective observers.

Ben Tracy: And picking up on that, I will admit too when I first started on this beat, feeling some of those issues of like, oh wow, this almost does feel like you are taking a side. And that’s a very simplistic way of looking at it.

I’ve really gotten over that because honestly, it’s only activism or you only can think of it as activism if you really do believe there’s still this debate over the science. And once you believe that there isn’t a debate over the science, you’re really just reporting facts like you are for other stories. And if people want to view that as activism, that by reporting scientific fact you are picking a side, I think that’s more on them and how they’re consuming the information than it really is on us as journalists.

Now, I think there are ways where you can step over the bounds of journalism as well, and I think we have to be very careful not to do that because then you’ll lose credibility. But if it’s really just about the science and the reporting, I let that go a while ago because otherwise you just stay stuck in that trap of not feeling like you really can report on anything.

Kyle Pope: When we talk about journalists pushing, I like to think back on some of the great moments of journalism, like reporting on the Vietnam War, reporting on the casualties, which was seen as almost a disloyal move by a journalist at the time, and they got a ton of pushback. Same with covering the civil rights movement, a ton of pushback. People thought it was inappropriate, same with Watergate. All of those in hindsight, are now among great moments of journalism. We look back at them and say, “I want to do that, and I hope that I can have the courage to do what those people did.” And so I think it’s just important to keep that history in mind that sometimes, what we do isn’t incredibly popular and there are going to be people who are pushing back on it, but it doesn’t mean that it’s not important. And we have people who came before us. They have our back is the way that I like to think about it.

We’re going to begin to take questions shortly from those of you who are watching. Please put your question in the Q&A. We’ll get to as many of them as we can. Ben, let me ask you, I brought up this issue about how to tell these stories for television and how the real constraints on time and on reliance of visuals, and we’ve all complained about polar bears and smokestacks and how that has become a cliche in telling climate stories. But what do you think about in terms of what you can show to make this stuff resonate? And also you mentioned solutions in your earlier comments, which is something we hear a lot about today because it’s a way for people to look past the pessimism and look past the idea that this is just too big for any of us to get our arms around. So can you tell me when you approach a story, how you think of those two issues, both how you’re going to show this story and how to think about solutions that might apply?

Ben Tracy: I thankfully work with a very talented producer, Chris Spender, who is always thinking of the visuals. He’s really always thinking of how are we going to make this a TV story? Because I might get into a wonky phase where I’ve read something that I find very interesting, and I’ll come to him with that idea and he’ll say, “Well, if you worked for a newspaper, that’d be a great story, but how are we going to tell that on television?” And it is a challenge.

I mean, two pieces that always come to mind when I think of how hard it is sometimes to tell these pieces on TV as we did a piece about methane, which by its nature, is an invisible gas, so that’s a hard thing to show on television. And we did a piece about carbon offsets, and we really had to think through how are we going to tell these stories? And for the methane story, we found scientists who were flying around on a plane to detect leaks in the Permian. We used satellite imagery, all sorts of stuff. For the offsets piece, we set that piece in a forest in Oregon that was set aside as carbon offsets and people were buying to offset their pollution and the forest burned down. So we went to the forest that burned down that was supposed to be sequestering people’s carbon. So there are ways to tell them, I think, on television, you just have to get a little more creative.

When it comes to bringing it back to politics, I think that challenge becomes even greater because politics coverage on TV can be a little boring in terms of its sound bites of people at podiums, it’s interviews, man on the street stuff with voters. So you have to think of different ways of covering that as well, which I think some of that speaks to why we’ve really tried to go into the solution space, not only to your point of letting people know that there is hope here, we know what to do. It’s a matter of can you do it and are you willing to do it?

But then also going back to our talk about the activism versus journalism, I think that comes into play there with solutions too. Not every solution is legitimate. And I think part of our role as a journalist is to interrogate those solutions and say, “Okay, even if technically this worked, can you scale it? Is it going to be cost-effective? Is this really going to move the needle in the timeframe that the needle needs to be moved?” So I always think of that too when we’re talking about solutions that it’s not good enough just to find a solution out there. Does that solution really matter?

Kyle Pope: Yeah. Thank you. So I’m going to turn to Q&A. First question comes from a colleague of ours from Pakistan who’s asking, “What is the advice for journalists from the global south who want to connect local climate impacts with the US elections?” Basically how to look at the US elections and what its impact will be on communities that are impacted around the world. Any thoughts on that?

Margaret Sullivan: I mean, I guess I would say that it’s a great case of trying to separate out the consequences from the odds, not who’s going to win or anything like that, but how would this play out? And I don’t think you’re into the land of speculation. You can actually report that as a story. How would a particular election, how would Trump versus Biden play out for climate if that person were to win? And I mean, I think that’s a great… And what are the consequences? What are the effects for the rest of the world? So I don’t know. I mean, I’d read that story and I guess that story has probably been done, but it could certainly be done more.

Ben Tracy: And I think it’s a really appropriate story because it does go back to the stakes of the election, that if we were to enter into a period of four years where climate policy in the US is basically dismantled and emissions cuts are not a priority and regulations are taken down, the impacts of those will be most pronounced in other countries, not necessarily here in the United States first and foremost, it’s the countries that are already suffering some of the worst impacts of climate change and have the least ability to respond.

So certainly I think tying the impacts folks are seeing in places like Pakistan or India or Bangladesh, anywhere in that part of the world, and there’s countless others to mention, to what the policy of the United States is, is really important. And also goes back to what I said at the beginning, and this we don’t know yet, but if we do get to that point where the US has a change in leadership and there’s a real step back from current policy, how does the rest of the world respond to that? Do people still say, “Okay, well, despite that we’re going to keep doing what we said we’re going to do?” Or do they say, “Well, given the timeline here folks, if the US isn’t playing ball, then let’s all just do our own thing and see how it shakes out.”

Kyle Pope: And just a reminder of the fact that Mark flagged at the very beginning, fully half of the world’s population is eligible to vote this year. So all of these climate issues are going to be up for discussion. Here’s a question from our friend and former colleague of yours, Ben Al Ortiz, a former producer at CBS, “What if instead of trying to compete directly with the horse race coverage, should we be paying more attention to the many aspects of climate change that are independent of election cycles, like scientific research, continued development of renewable energy, the transition to electrical transportation, all of which are well underway and will continue because private business and states are heavily invested and it’s somewhat separate from politics?” It does remind me of your battery story, but you want to talk a little bit more about that.

Ben Tracy: Yeah, I totally agree with that. I think it’s probably a both kind of answer. I think we should be doing that. And what Al just described there, I would say is very much kind of our general approach to our coverage and what we do day in and day out. I think this year, there is an expectation, and I think as journalists, we can’t ignore the fact that this major election is going on that has a huge impact on this subject that we cover. So I think it’s both, but to Al’s point, I don’t think every story needs to be politics just because we’re in an election year. But I don’t think you can ignore the politics.

And let me give you an example. We just did a piece about some of the challenges facing the offshore wind industry, and as I’ve been out doing these stories, I’ve been asking people about the upcoming election and what happens, how do you see this playing out if Biden wins? How do you see this playing out if Trump wins? Assuming those are the two candidates. And people will give you different thoughts. But for instance, on offshore wind, a couple of the executives that I talked to, they were pretty candid and said, and this was an off-the-record conversation. So I won’t tell you who it was or the company involved, but just to give you a sense of it, they said, “Yeah, it’s the kind of thing where a president, if they’re opposed to it, they can basically just stop the federal permitting in these waters because almost all of these things are being built in federal water.” So they were looking at an industry that could be frozen in place just as it’s really trying to get off the ground.

So I think as we move forward when we do stories, I think we’ll be looking for ways to bring in politics or the stakes of the election when they’re appropriate to the thing that we’re covering. And then I think there will also just be stories that are very politics-centric about what voters are thinking about certain issues or what the candidates are saying. It’s somewhat hard though, because having gone to many Trump rallies back in my day, his thoughts on some of these climate issues are not particularly nuanced. A lot of it comes down to windmills causing cancer and light bulbs not looking quite right, or shower heads not having enough pressure. So I think we need to not let ourselves get caught in that space of these things that don’t really matter to be talking about and really do talk about what some of the policy implications could be.

Kyle Pope: So “drill, baby, drill” isn’t subtle or nuanced?

Ben Tracy: Well, but as a journalist, in some ways, having that stark of a contrast is also helpful because it’s not like, well, they’re kind of similar on this. There are big differences, and I think our job is to point out the differences. It’s not to say which differences the one you should choose or the one you should align yourself with, but here’s the consequences of those decisions.

Kyle Pope: Margaret, we have several questions about climate and local reporters, which is something near and dear to your heart. One person asked, “What is a way to bring this home?” And I read your amazing book called Ghosting the News, and it makes the argument that the decline of local news means that we’re getting a lot less coverage of kitchen table issues and issues that are really critical to people’s daily lives. And that void has been filled by big national debates and politics debates and stuff. And I assume the same applies to climate coverage and how it’s impacting people on the ground at home. But can you talk a little bit about the link between those two things?

Margaret Sullivan: Yeah. So we know that local news has declined a lot, that particularly newspapers have shrunk, have gone out of business, that two local newspapers are going out of business every week in the United States. Now, most of those are weeklies, and I’m not suggesting they were doing deep climate coverage before, but overall, this is an ecosystem that is looking really different now than it was even 10, 15 years ago. So when I was the editor of the Buffalo News, we had a full-time reporter covering the environment, and sometimes, two people, and that was local. So they were covering the State Department of Environmental Conservation, and they were covering… I don’t know, I mean it was after Love Canal happened, but that was a huge story at the time. You really don’t have that anymore. That doesn’t exist.

So in order to cover these issues, you have to make a very… You don’t have beat reporters who are doing this stuff as a general rule. So you have to be very clear, I think newsroom leaders at nonprofits, at newspapers that still exist but are much smaller at local TV stations, at public radio, all these places, they have to make some tough decisions about what they cover. And so I think it really behooves them to be thinking about climate as one of the things that they still want to cover despite their shrunken stats.

And I’ll just add that one of the things that worries me the most about news deserts and about the diminishment of local news is that as a population, overall, we have lost sort of this common ground that we all can stand on, that we might disagree with each other, we might have different opinions, but we kind of understand this is what’s going on in our communities and this is what’s going on in the world. And then we can argue about it from there. To a large extent, we don’t really even have that anymore. People are in their filter bubbles. They’re getting their news from their Facebook groups, or in some cases, these pink slime sites that masquerade as local news and all of that. There’s a lot there. But as it impacts climate coverage, I think to some extent, it’s the loss of staff, the very extreme loss of staff, even in major metro areas, and certainly in places that had not too much local news to begin with, and now they probably don’t have any.

Kyle Pope: Yeah, I always thought that the decline… I mean, when you talk about the common language, I mean you can’t really argue when somebody’s writing about what time the library opens or what the score was on the high school football game. It’s sort of indisputable and there’s no question of media trust on the issue. When we get further away from people’s lives that the trust issues come into play, and I think these two things are very much related.

Margaret Sullivan: Yeah, I mean, we know from studies that local journalism is significantly more trusted than national and for the very reasons you mentioned. And trust is a big problem, so it’s tough to see the thing that’s… It’s like, it doesn’t make sense in some ways. The thing that’s more trusted is the very thing that’s going away, but trust doesn’t add up to a reasonable and sustainable business model unfortunately.

Kyle Pope: Somebody asked a question further on this local issue, which is something that I think we don’t talk about enough. Which is how would you recommend doing local reporting on climate in a rural community where climate skepticism or even denial is high?

Margaret Sullivan: Yeah, I mean it’s such a challenge. I think it’s challenging in communities right now to even cover the school board. So maybe we come back to what Ben said, which is even though science is questioned a lot, to still try to relate it to facts that are generally agreed upon. And to constantly be underlining that, that it’s not somebody’s opinion anymore. This is what we know and to treat it that way. But I don’t know. I mean, that’s a great question and I’d like to think about it some more.

Kyle Pope: Just before you go on, somebody asked a version of the same question. Which is this person says, “I’m in a conservative state with the GOP super majority, and most if not all the GOP state lawmakers don’t believe in climate change and regularly refer to it as a hoax. What advice or insights can you offer on how to cover climate in that context?”

Ben Tracy: I think that’s hard. I think it does come back though to reporting just the facts of both the science, but I think also the facts of what people in a local area are experiencing. I think most people are experiencing the climate story through their own weather. And we know that not all weather is climate, but certainly climate change is driving some extreme weather events and changes in the weather.

I noticed this just talking to folks back in Minnesota where I’m from, where in recent weeks it’s been 52 degrees and there’s no snow on the ground, which is just crazy. That’s an entry point to talk to somebody about climate change. They know that’s not normal. They know that when they were a kid, they had two feet of snow that they were building forts out of, and now they’re lucky if they get a couple inches out of some of these storms.

So I think there are ways to localize this, whether that’s the leaves on the trees coming out a month earlier than they did 20 years ago or whatever it is. I think when you can kind of bring some of these climate impacts down to things that people can see with their own eyes, they can experience in their own neighborhood, those can be an entry point. Now, obviously not every story is going to be as simplistic as telling people when fall and spring happen, but there are entry points for that.

If you’re covering politics in a place where the majority of the elected officials just deny that climate change exists, that’s tough. And I guess your job as a journalist is just to confront them about that and to present the science and say, “What is it about this that you don’t believe?”

Unfortunately, what often happens now is those same politicians are probably not going to do a sit down interview with that reporter who can ask those questions. They’re kind of let off the hook by the fact that they can say their soundbite and then never really be pressed on the specifics of what it is they do believe. Or how they do explain some of the things that are happening if it’s not climate change. And that I’m not sure how we get around. I think that’s just kind of a function of our system that there is a whole other media ecosystem that they could go to and have a sympathetic hearing and never really have to be pressed on some of these issues.

Kyle Pope: Here’s a question that I think is important. This is about climate activism and how to cover it. Climate activism is a driving force in American politics. Are reporters less interested in covering climate activists because they feel the coverage will read as overly partisan? What do reporters need from climate activists to be able to tell the stories of the communities those activists represent?

Margaret Sullivan: I mean, I do think that the fear of appearing partisan enters into all of this coverage, so it certainly enters in here. But I mean, one thing about journalists is they are interested in telling good stories. So if you’re trying to appeal to them, I think presenting interesting people, interesting situations, conflict and drama. You can’t really expect journalists to become authors of white papers or something like that. They’re going to want to tell stories that are interesting to their audiences and interesting to their bosses. So I think to have that mindset when you are pitching stories or when you’re telling somebody about a situation that you’d like to have coverage on, is to be realistic about the kinds of stories that whatever outlet it is actually does.

Ben Tracy: And I think it also depends on what the activism is. Is the activism a mom in Louisiana who lives near an LNG facility or a petrochemical plant and she’s fighting that on behalf of her kids who are sick? Or is it just covering a protest against fossil fuels? I’m not saying the latter thing is not important. I just think it depends on what the activism is.

We’ve been kicking around a story about the increasing activism amongst some of these more disruptive protests where people are stopping traffic or gluing themselves to the court of the US Open. I think that’s an interesting topic to cover because I wonder how much of that is getting people’s attention, how much of that turns people off? I’m just kind of intrigued by that as a journalist. So I think that’s a way of covering activism, not through a lens where you’re kind of taking a side on it.

Kyle Pope: We only have a few more minutes, but Margaret, I wanted to ask you in part of your new mission in the center that you’re at at Columbia, is to look at ethics security, which includes disinformation aimed at journalists and misinformation. The climate world is rife with this. I mean, we’re dealing with decades of propaganda from the fossil fuel industry aimed at the press. I’m wondering what your assessment is of how, maybe in general, but if you have specific information about climate, but just in general, how equipped newsrooms and journalists are to face this and deal with it. What are you finding so far?

Margaret Sullivan: Well, I mean, I think that one of the… The purveyors of dis and misinformation are getting better at it all the time. And the public isn’t particularly well-equipped to parse out what’s true and what’s not true and what’s a deep fake and what’s actually reality. So while we can’t make ourselves into a classroom for news literacy, we can kind of do some explaining to the public about what’s real and what’s not real and how to tell the difference. I mean, I think that that can be done in regular, as a part of the reporting, and I think it’s really, really important.

I mean, on the bright side, I think people do understand that there’s a lot of false stuff out there. A lot of politically motivated disinformation, a lot of stuff that looks like news but isn’t, and they don’t necessarily have any place to turn on this. So we need to start to fulfill that role in the course of our journalism.

Kyle Pope: Ben, do you have any thoughts about fighting disinformation?

Ben Tracy: Yeah, I mean, I think it’s super important. I think it goes back to just what I’ve said a couple of times now about returning to the science. And there’s a question in the Q and A there that I just want to bring up. Somebody asking, saying, “I’m not questioning your objectivity, but how would you respond to critics who might challenge your participation as a journalist in this very forum?” And I think it goes back to what Mark often says at the beginning of these things, and he says it much better than I can. So if he wants to say it, feel free. But he always talks about being a member of Covering Climate Now as a journalist or as a news organization, doesn’t mean that you have to report certain things. I think the only threshold is that you just don’t deny the science. And I think those of us who cover this for a living, that’s kind of the baseline for this coverage.

But there is no company line that we have to tout by being in a forum like this or companies being a part of it. So just for anyone who’s maybe new to this and not familiar with Covering Climate Now, I just wanted to flag that question. I do think it’s important, and it does go to the larger issue though of this sometimes feeling like you are straddling this line of activism. But I always do take it back to the fact that it’s not activism if you’re just reporting what the scientists are saying.

Kyle Pope: Yeah. Thank you for addressing that. This has been fantastic. Thank you both for being here. Thanks to everybody for their questions. Mark’s going to come in just a second. Just a few housekeeping things. First, Covering Climate Now publishes two newsletters, one on politics and climate called Climate on the Ballot, which you can sign up for on their website coveringclimatenow.org. We also have a weekly newsletter called The Climate Beat, which just addresses the big issues in climate that week.

Also, a lot of you know this, but before I let you go, I want to remind you that we’re accepting entries for the 2024 Covering Climate Now Journalism Rewards, which is aimed at elevating climate coverage that you may not know about or may not have seen. And we’re thrilled to be able to do it. That deadline is March 1st at midnight, so we’ll drop a link in the chat. Please submit your applications. Thank you both again. This was really, really great. Over to you, mark.

Mark Hertsgaard: Thanks, Kyle, and again, thank you Margaret Sullivan and Ben Tracy for a really stimulating conversation today. That’s Ben Tracy, the National Environment Correspondent for CBS News, Margaret Sullivan, regular columnist for The Guardian and [inaudible 00:56:44] I think we can say at the Columbia University these days.

One quick thought about some of the questions that have been raised today about how do we cover climate change in a rural area where there’s a lot of climate denial. We’ve talked to Covering Climate Now before about sometimes the similarities between what we as a profession did during COVID to what we could be doing now with climate. And during COVID, I think most of us were very careful to ground our coverage in the science. And when political interests tried to politicize the issue, I think that we held our ground and we understood that we had to be true to the science, ground our coverage in the science. If a politician wants to go off on it, that’s their business. We mustn’t let that censor what we do as journalists, which is to report the facts and let the facts lead where they may. So perhaps that will help some of us as we approach this coverage going forward.

And in the meantime, we urge all of you to check out the Covering Climate Now website. Come and join our community of journalists on the beat. As Ben says, the only requirement is that you be a bonafide journalist and that you respect the science. So with that, I again, thank our panelists. I thank my esteemed colleague, Kyle Pope and Anna Hiatt and Karin Kamp, who’ve been running the show behind the scenes, for making this a very smooth hour. And on behalf of everyone at Covering Climate Now, this is Mark Hertsgaard saying, “I wish you all a very pleasant day.”