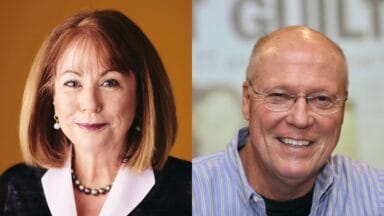

If you were a reader in Florida, starting a few years ago, you might have noticed an uptick in climate-centric op-eds in your local newspaper. That’s thanks in large part to Rosemary and Tom O’Hara, veteran newspaper editors who launched and supervised The Invading Sea, a collaborative effort to hasten the climate conversation in their state. Through The Invading Sea, newspapers across Florida shared opinion content with one another and gained access to writing from an array of informed voices. The O’Haras, who are married, announced their retirement this spring, handing over The Invading Sea’s reins to Florida Atlantic University’s Center for Environmental Studies. Covering Climate Now spoke with the O’Haras about the virtues of collaboration in a precarious media industry, the climate conversation in Florida, and the climate subjects that resonate most with readers.

The conversation, with CCNow deputy director Andrew McCormick, is part of a regular series of Q&As in which CCNow speaks with journalists about their experiences on the climate beat and ideas for pushing our craft forward. The O’Haras’ comments have been edited for length and clarity.

What did you aim to achieve when you started The Invading Sea?

ROSEMARY: We started The Invading Sea in 2018, when I was the editorial-page editor at the Sun Sentinel in Fort Lauderdale. South Florida is the tip of the spear for climate change, so together with my counterparts at the Miami Herald and the Palm Beach Post, we decided to do something to raise awareness and increase public engagement on climate. We focused on sea level rise at first—our tagline was “Can South Florida be saved?”—and then later expanded to the environment and climate change in general.

Because staffs had become so reduced over the years, it was helpful to know that we could count on one another to deliver editorials, well-edited op-eds, or even editorial cartoons. Which, in many ways, was unprecedented: We were competing newspapers, owned by competing companies, but still, we joined hands and made a splash. We were able to create a drumbeat of content on an important issue that I think we wouldn’t have been able to do otherwise, individually. We also partnered with the local public radio station, WLRN, which had us editorial-page editors on once a month to talk about climate. As we grew, the drumbeat became more of a symphony.

TOM: So, initially it was just those three South Florida papers. After about a year, we thought, “This really needs to be statewide.” The Tampa Bay Times, the Orlando Sentinel, and the Gainesville Sun came on board—and eventually we counted twenty-six newspapers across the state as partners of The Invading Sea. I took on editing duties for op-eds sent directly to The Invading Sea. People realized that when they sent pieces directly to newspapers they usually didn’t hear a peep back—newsrooms are up to their eyeballs every day trying to get a paper out—whereas we looked at pretty much everything we were sent. It was more efficient for those writers, too; instead of just one paper, a piece sent to us had a chance of ending up in quite a few. We started getting pieces from all kinds of people, from high schoolers to elected officials.

As Rosemary suggests, the impulse in the industry is often toward competition. What was your pitch to outlets? Did you encounter any skepticism about this sort of collaboration?

ROSEMARY: Well, although we were competitors, I knew and had worked with both Nancy Ancrum, the editorial-page editor at the Miami Herald, and Rick Christie, who is now executive editor at the Palm Beach Post. It helped that we had relationships and trusted one another’s standards.

As far as our publishers went, we didn’t go seek permission. We just did it. When we did eventually tell them, they were excited about it, in part because we were already getting great feedback from the community.

TOM: And getting other newspapers on board was pretty easy, actually. You say to papers, “How would you like some thoughtful content that you won’t have to screw with much?” Again, because of the diminished state of newsrooms, I think just about any editor is going to say, “That sounds pretty damn good to me.”

ROSEMARY: So few newspapers run robust opinion pages anymore. Publishers will say, “Oh, people don’t want to be told what to think” or “The political divide means half the audience is alienated anyway, so what’s the point?” But in truth, or at least in equal measure, stripping down opinion journalism has been a cost-cutting move. So we were glad to be getting pieces out there and saying, you know, “Here’s what we think about sea rise and climate change. After reading the facts that explain our positions, what do you think?”

Florida is often in the national spotlight, but due to “culture war” questions and the latest on Disney and DeSantis, as opposed to a national wake-up call on climate. For people reading this who are not in Florida, does the public discourse there feel more grounded than what we might see on TV? What’s your sense of the public pulse on climate change?

ROSEMARY: I think awareness of climate change is greater in Florida than in much of the rest of the nation. Eighty percent of Floridians live on the coast, and they’re seeing things they’ve never seen before. We have these storm drains, for example, that water is meant to pour down into during high tides; well, now water levels are so high that we often see water coming up through those. So I think most people believe in climate change. The questions are: Do they believe it’s human-caused, and what do they believe we should do about it?

About 90 percent of Democrats here believe climate change is human-caused and that actions we take can help solve it. That number is lower among Republicans, around 35 percent, but it’s growing, especially among younger Republicans. Another big difference in Florida, compared to some other parts of the country, is that the business community has gotten engaged. In South Florida, the chambers of commerce and the economic-development folks see what’s on the horizon, in terms of threats to their businesses and property values and whether they’ll be able to afford property insurance and flood insurance. They’ve started pushing Tallahassee to do more—and now, in the last couple years, we’re hearing more from the state capital about resilience, and we’re seeing more money on the table to address storm surge and protect ourselves.

The problem is that many lawmakers, including the governor, won’t say the words “climate change.” They’re not willing to bite the bullet and acknowledge what’s causing this—much less that we need our power companies to reduce carbon emissions.

TOM: I’m a bit more pessimistic than Rosemary on this. People care all of a sudden about climate change when there’s a hurricane, or when we get twenty-five inches of rain in just a few hours, like we did last month in Fort Lauderdale. But I suspect most people in Florida know very little about climate change—they don’t know what to think about whether or when it will affect them, and many likely think the problem is too big to even worry about. Government officials are aware of the science. But I think many conservative leaders think the threat is overstated. Many think that technological innovations will solve the problem—that higher seawalls will alleviate the threat until technology finds solutions.

A thousand people a day are moving to Florida, most of whom are old people with money. They’re moving here because taxes are low, and they don’t want to hear that the government needs money to help reduce the state’s carbon footprint.

Oddly, perhaps, I think capitalism is our best hope to prompt change in Florida. People will take note when their insurance bills skyrocket, when gas prices soar and power bills keep climbing; people will embrace change if they can save money. Businesses will embrace clean energy if they can make a profit. The power companies, for example, are going to find out they can make more money with solar than they can burning oil and natural gas. When banks stop issuing thirty-year mortgages because homes in Florida aren’t going to last thirty years—bankers are in the risk business, and they’re not stupid—that’s when we’ll see change.

ROSEMARY: At the end of the day, so much comes down to Florida. I think there’s a sentiment among activists and others who are really wrestling with the climate problem here that if only Florida would lead on climate, we would lead the nation, and in turn our nation would lead the world. We’ve made strides in the last couple years, but the problem is we don’t have time. Things need to be done now to avoid the worst of what’s coming.

In your years with The Invading Sea, what subjects did you notice resonated most strongly with audiences?

TOM: Dead manatees. Readers love those creatures, and lots of papers would run manatee-related pieces, which provided us with many teachable moments. The climate connection is that water pollution largely caused by the warming waters is killing the seagrass that manatees eat by the ton to survive.

People do read about hurricanes and other major storms, and those are also teachable moments—when you’re stuffing towels under your front door, you want somebody to explain what the hell is happening. The two hurricanes of 2022, for example, Ian and Nicole, both caused an enormous amount of damage, and climate experts say both storms were made worse by the warming atmosphere and warmer waters.

And the legislative sessions always generate a lot of op-eds, particularly from climate activists.

ROSEMARY: You know, on the legislative sessions, we would hear a lot from readers, “You just have it out for DeSantis. You never say anything good about him.” That’s a concern we should listen to. Yes, the government isn’t moving fast enough on climate change, but that doesn’t mean nothing is getting done. So, at the end of the last legislative session, I wrote a column called “Good and bad climate news from the Florida legislature”—and I think a lot of readers were surprised to learn that there was any good news. Nothing is all black-and-white. We shouldn’t pull punches, but I do think we’ll bring more people into the conversation if we don’t focus only on criticizing governments for what they’re not doing.

Are there any lessons you’ve taken from The Invading Sea that you think could help journalists elsewhere serve audiences better on climate?

ROSEMARY: It’s important to hear from a lot of different voices on climate change. One of the things I’m most proud of with The Invading Sea is that we were able to give a platform to so many different people who care about climate change in our state.

I also think The Invading Sea shows the importance of collaboration between news organizations. There’s a lot of climate news out there to cover, and with smaller staffs, outlets aren’t always going to have reporters to cover it. We can help fill each other’s coverage gaps. If one outlet doesn’t have a reporter capable of explaining why your property insurance has doubled in five years, another newspaper might—and ultimately that’s what’s going to serve readers’ understanding of what’s going on. Look at the state of the news industry, and it’s clear that most outlets can’t make it alone. So journalists have got to start doing things differently and understand that we’re in this together.