This Covering Climate Now memo is meant to help all of us as journalists think through how to cover this November’s COP26 global climate summit with the urgency it deserves. The summit, scheduled to take place October 31 to November 12 in Glasgow, Scotland, is one of the most important diplomatic meetings in history. As climate chaos explodes around the world, world leaders face what United Nations Secretary–General António Guterres has called a “code red for humanity”; the world must slash greenhouse gas emissions immediately if humanity is to prevent the worst of what climate change has in store and preserve civilization as we know it.

Covering Climate Now is organized by journalists, for journalists. Below, we outline how journalists everywhere can meet this historic moment with robust, insightful coverage. Whether you’re covering COP26 on the ground in Glasgow or remotely via video link, this memo will equip you to help your audience understand what’s at stake and why this summit is of the utmost importance to each and every one of them. (For information on accreditation, Covid-19 restrictions and other logistical issues, see here.)

Why Is COP26 More Than Just Another International Meeting?

COP26 (26th UN Climate Change Conference of the Parties) is the follow-up to the 2015 Paris Climate Change Conference (COP21), at which the Paris Agreement was signed. Adopted by 196 countries, Paris set a goal of limiting average global temperature rise to “well below” 2 degrees Celsius, and preferably 1.5 C, compared to pre-industrial levels.

In advance of COP26, countries presented the United Nations with the first Nationally Determined Contributions, which are countries’ plans for achieving the 1.5 C target and other goals of the Paris Agreement. Parties to the Paris Agreement must prepare NDCs every five years. (The NDCs were scheduled to be delivered in 2020, but COP26 was delayed one year due to the Covid pandemic.) The NDCs released on September 17 fell grossly short of what science says is necessary. Instead of emissions falling by 45 percent by 2030 compared to 2010 levels, they would increase by 16 percent, putting the planet on a “catastrophic pathway” towards 2.7 C of temperature rise, Guterres said.

Humanity must take big, ambitious global action now to limit future temperature rise to a survivable amount. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has made this point repeatedly—and did so again when it released its most recent findings, the Sixth Assessment Report, in August 2021. To limit future temperature rise to 1.5 C, heat trapping emissions must be cut in half within 10 years and eliminated completely within 30 years—steps that require ambitious and rapid change across nearly every sector of society.

COP26 amounts to a deadline for US president Joe Biden’s budget reconciliation package. Biden has pressed Congress to pass a budget bill that includes a panoply of measures—from tax credits to buy electric vehicles to incentives for utility companies to quit coal and gas in favor of wind and solar—that are fundamental to the president’s goal of cutting overall US emissions in half by 2030, as science requires. Failure to pass that bill would damage the United States’ credibility as a climate leader and Biden’s ability to press other countries for strong action at Glasgow.

How Do Journalists Tell the COP26 Story?

There’s no one way to tell a story this big, and every newsroom is different. Some outlets will have journalists in Glasgow; some will cover the summit from afar via video link.

Many smaller and local outlets might consider leaving COP26 coverage to larger, national newsrooms—but that would be a missed opportunity for an event of such universal importance. Consider how small and local outlets provide valuable coverage of national elections. Newsrooms everywhere can point out how the decisions made at COP26 are relevant to their audiences. Interview local scientists, activists, and other experts who can explain how climate action—and inaction—will affect your community. Here are some tips for planning your coverage:

Commit to covering the summit robustly. Run as many stories as possible and give them big play—at the top of your homepage and front page, early in your broadcasts, and frequently on social media platforms. Remember: This summit is about the future of life on earth—it’s hard to imagine a more important story.

Although COP26 is a global summit, there are climate impacts in every locality, making this a story for every newsroom on earth. Climate summits bring together issues of science, politics, economics, and justice. The best journalism will humanize and localize these issues, using human-centered stories that illuminate the social forces at play.

Don’t wait until the summit’s final days to begin covering COP26; that’d be like not covering a presidential election until Election Day itself. A news event this momentous requires abundant advance coverage, starting now and continuing through the end of the summit. There are plenty of news pegs ahead.

What Are the Main Story Lines at COP26?

Covering Climate Now suggests that newsrooms frame their coverage around the essential question, “What’s at stake?” Here are three themes to help answer that:

- 1.5 C is the most important number at COP26.

- Climate justice is both imperative and self-interested.

- Solutions abound—but so do political barriers.

Below are explorations of each of these three themes, including pertinent background and framing that could help spark story ideas or generate leads.

1.5 C is the most important number at COP26.

The 2015 Paris Agreement set the goal of limiting global temperature rise to “well below” 2 C over pre-industrial–era levels, and preferably to 1.5 C. The need to get as close as possible to 1.5 C was made starkly clear in the IPCC’s Sixth Assessment report released in August 2021.

- The Paris Agreement enshrined 1.5 C as the preferred goal, thanks to demands from the Global South and despite resistance from big emitters.

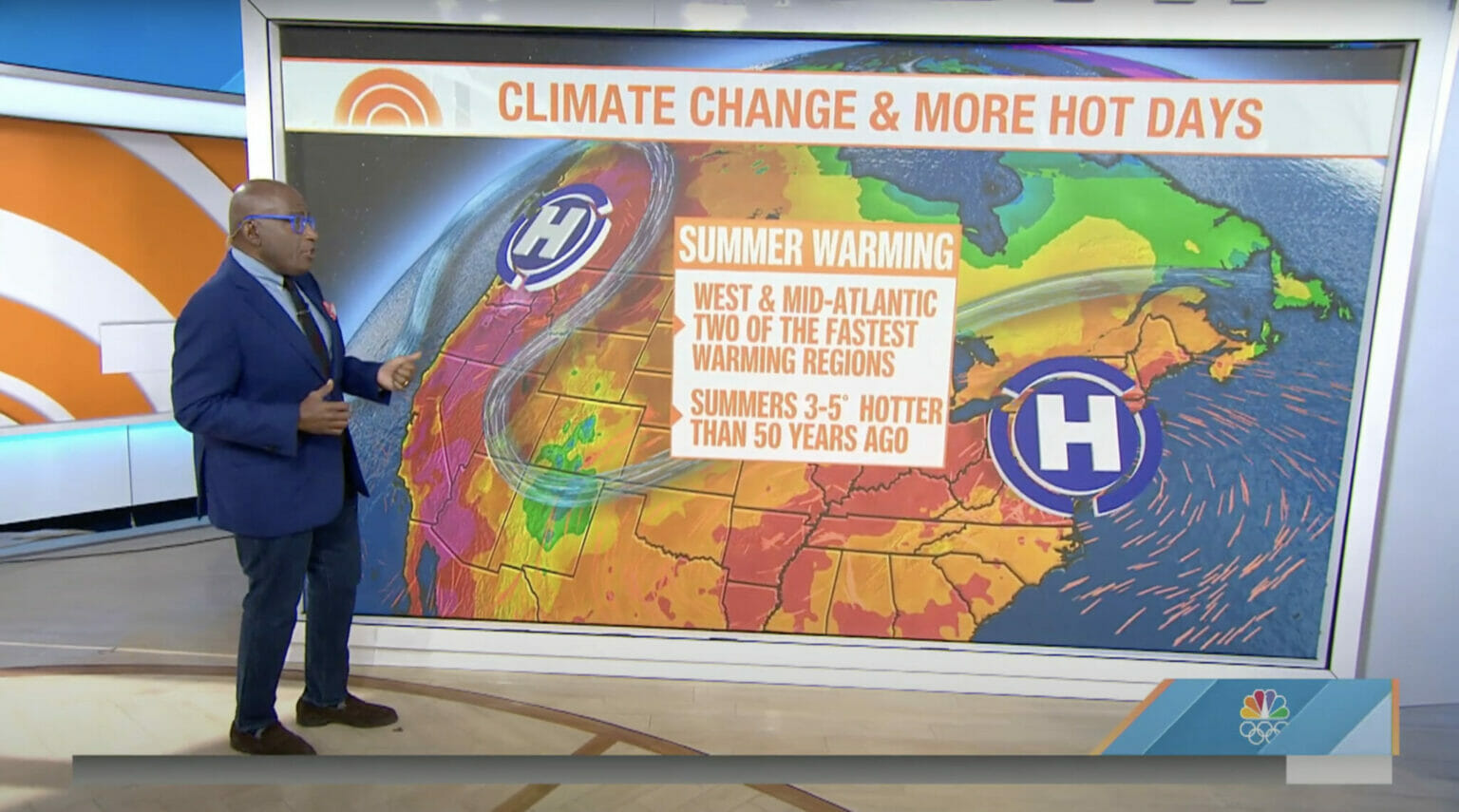

- We’re at 1.1 C now, and already extreme weather events are far more frequent. For example, extreme heat waves like the ones that broiled the North American West in 2021 now occur five times as often as they did historically, the IPCC found. If global temperature rise reaches 2 C, they’ll occur 14 times as often.

- Additional warming is already baked in. Because humanity cannot end emissions overnight, some additional warming is already unavoidable.

- Hitting 1.5 C is still possible. Halting emissions of carbon dioxide, methane, and other heat-trapping gases quickly enough to stay within the 1.5 C target is still possible. However, it will require “unprecedented, transformational change,” said Ko Barrett, a vice chair of the IPCC. To have even a 50 percent chance, 90 percent of the world’s coal reserves and 60 percent of the oil and gas reserves must be left underground, unburned, the Guardian reported.

Climate justice is both imperative and self-interested.

Conflict between rich and poor has hampered progress at every UN climate meeting since climate change first took center stage at the 1992 Earth Summit. Rich countries have by and large refused to limit their consumption of fossil fuels or pay compensation for the resulting damages, while poor countries have insisted on their right to emit as many greenhouse gases as needed to lift their people out of poverty.

- The poor are suffering first and worst. In countries and communities across the world, the effects of climate change, including heat waves, drought, and rising seas, are hitting the poor first and worst, even though they have emitted a tiny fraction of the greenhouse gases causing these impacts.

- Rich countries’ current per capita emissions are exponentially higher than those of poor countries. Burning fossil fuels for many years helped enable rich countries to get richer.

- The average American’s annual carbon dioxide emissions outstrip people in developing countries. They are equivalent to the emissions of 35 people in Bangladesh, 51 people in Mozambique, or 581 people in Burundi.

- Developing countries may take longer to peak and cut emissions than wealthier countries. This understanding was built into the Paris Agreement and the NDCs, the first round of which will be presented in Glasgow.

- The United States is the leading cumulative emitter of greenhouse gases since the Industrial Revolution. China recently overtook the US in the distinction of highest annual emitter, but it’s cumulative emissions that matter to the atmosphere. Poor countries therefore argue that fairness dictates the US and other long-industrialized nations should do the most to fight climate change.

- Global South governments will call for “loss and damage” compensation. This call for compensation for climate impacts that disproportionately affect the poor will likely be a contentious issue at COP26.

- Climate justice is local. Climate justice is not solely a matter for global negotiations; it’s also an issue within countries and local communities, too.

Climate justice is not only a matter of fairness; it is in rich countries’ self interest. If poor countries lack the financial means to choose a green- over a brown-energy future, there is zero hope of limiting temperature rise to 1.5 C. Should that come to pass, the rich, too, will suffer, as this year’s heat waves, wildfires, and storms harshly demonstrate.

Solutions abound—but so do political barriers.

Scientists use the term “climate emergency” both because overheating the planet could end civilization as we know it and because the necessary remedies must be applied so rapidly. While climate solutions are abundant, countries and corporations invested in maintaining the status quo often create political barriers that delay or prevent the implementation of available climate solutions.

- The US Congress has thwarted ambitious climate action for decades, with Republicans still not accepting basic science. Before Glasgow, a big question is whether Biden gets the budget reconciliation bill, including its climate provisions, passed. If not, he’ll be hard pressed to portray the US as a climate leader at COP26 or pressure other big emitters to do more.

- Carbon states have strong-armed past summits. UN summits operate by what amounts to consensus, enabling some of the world’s richest countries and de facto carbon states (like the United States, China, Australia, Russia, Canada, and Saudi Arabia) to thwart progress by refusing to agree.

- Fossil fuel companies have buttressed carbon states. The wealth and power of companies like Exxon and Aramco have been perhaps the single biggest reason why decades of UN climate negotiations have achieved so little. (Little, but not nothing: The Paris Agreement, for example, put 1.5 C on the global agenda.)

- Rich countries have repeatedly failed to honor their promises, which threatens to be a major sticking point at COP26. An analysis by the anti-poverty group Oxfam found that rich countries provided only $19.5 to $22 billion in climate aid in 2018, the last year with reliable data. Developed countries pledged in 2015 that by 2020 they would scale up to providing $100 billion in annual aid.

- Restoring trust is essential for ensuring a successful summit. UN Secretary–General Guterres has warned that providing the $100 billion of annual climate aid is essential to restoring trust among developing nations, without which the summit could fail. John Kerry, US president Biden’s international climate envoy, has also called for rich countries to honor their pledge.

- Carbon fuel production is deeply embedded in national economies. Currently, carbon-based fuels supply roughly 80 percent of the world’s energy; over the next 30 years, that percentage must fall to virtually zero.

- Tax, subsidy, and regulatory policies in these carbon states lopsidedly favor fossil fuels. Decades of such favoritism have spawned domestic constituencies—from coal regions in China to Texas oil-patch communities—that pressure politicians to preserve the status quo.

Rigorous accountability journalism in newsrooms of every size, from local to international, will play an important role in helping audiences understand the barriers that have obstructed big, ambitious climate agreements.

How To Make COP26 Matter to Your Audience

COP26 will determine the conditions under which every reader, viewer, or listener and their loved ones will spend the rest of their lives. It’s hard to imagine a story that matters more than that. Below are prompts to help spark story ideas.

Inform audiences about how the government officials and corporations in their area approach the climate crisis. Do they accept climate science or deny it? Do they vote for or otherwise support taking climate action commensurate with the scale of the crisis, or do they slow-walk solutions and greenwash unsavory activities? Don’t forget that climate change is both a global and a local issue, and that local governments generally have a better record of confronting the challenge.

Explain what success or failure at COP26 would mean for people’s daily lives. A successful summit will boost clean energy, climate-friendly farming, and similar reforms, even as it darkens prospects for fossil fuels, industrial farming, and similar activities. What would such changes mean for your local economy? What kinds of new jobs will become available, and what jobs might disappear? Which civic, business, and political leaders are navigating these new opportunities? Is anyone making sure that coal and oil workers and their communities that are transformed by a shift to clean energy are provided with a “just transition” to the clean economy of the future?

Make the connection between powerful bad actors and your audience’s pocketbook. Partly thanks to fossil fuel companies’ 40 years of lying about climate change, mass awareness of the climate crisis has been slow to emerge, meaning that most governments have not faced the public pressure needed to overcome entrenched interests. Abundant investigative reporting has documented that fossil fuel companies were aware in the 1970s that burning ever more fossil fuels would catastrophically overheat the earth; their own scientists told them so. At the moment, taxpayers around the world are on the hook for hundreds of billions of dollars of climate damages—in the form of increased flood protections, health costs, and more—engendered by fossil fuel companies’ actions. Dozens of lawsuits have been filed demanding that companies help pay for these climate damages, an argument that may well surface at COP26.

Conclusion

This memo summarizes the basics, yet only scratches the surface of what journalists should know about COP26. If you’re still hunting for story angles or ways to begin thinking about the summit, consider the role of central and private banks (“follow the money” is always a good rule for journalists); food and forestry; so-called “net zero” emissions plans (and how to tell the difference between genuine and phony ones); the role of China, India, Brazil, and other high-emitting emerging economies; and not least, the role of civil society and especially young climate activists in prodding governments, corporations, and yes, the media to do more to preserve a livable planet.

In advance of and through COP26, Covering Climate Now will provide further resources for journalists, as well as Talking Shop webinars and press briefings related to the summit. Follow us on Twitter and Instagram, join our Slack channel (select “Individual member journalist”), and sign up for our weekly newsletter, Climate Beat, to make sure you don’t miss a beat. If you have questions please don’t hesitate to reach out to editors@coveringclimatenow.org. For more, visit www.coveringclimatenow.org/