Climate change is the defining challenge of our time impacting nearly every aspect of our lives, making it a story for every journalist in the newsroom. Audiences want to better understand climate change, its potential solutions, and what they can do about it. This guide is designed to help do just that. It covers the basics of climate change and provides sample language to help you include climate in your stories. Vea la versión en español de esta guía.

JUMP TO CLIMATE REPORTING GUIDE CATEGORIES

Key Terms

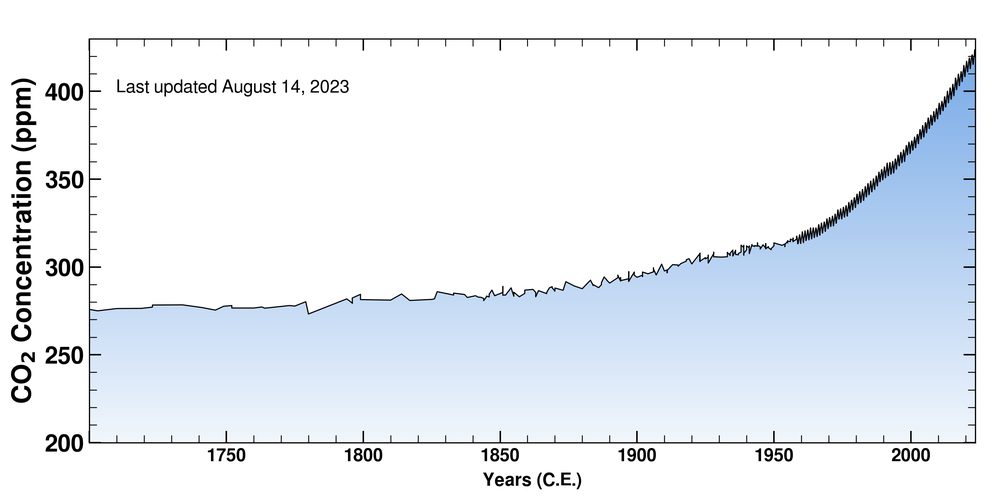

Global warming refers to the average rise in global temperatures since the Industrial Revolution when humans started burning more fossil fuels. When carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases build up in the atmosphere, they trap heat, causing the planet to warm, like a greenhouse. Land, ocean, and air temperatures are now warming at an alarming rate.

Climate change is occuring as a result of global warming and includes changes such as melting glaciers, rising sea levels, changing planting seasons and bloom times, and more extreme weather.

Weather vs. climate. Weather refers to conditions over a short period of time, like a few hours or days. Climate is the long-term average of weather over decades in a specific place. As climate scientist Dr. Katharine Hayhoe puts it: Weather is like your mood, and climate is like your personality.

Dig deeper: See the UN’s climate dictionary for more terms and concepts in accessible language.

Main Causes of Climate Change

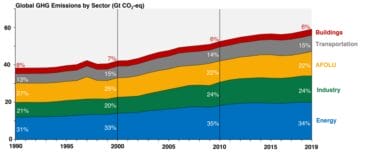

Source: The US Environmental Protection Agency. Data from IPCC (2022)

Climate change is primarily caused by:

- Burning fossil fuels such as oil and gas releases greenhouse gases (primarily carbon dioxide, methane, and nitrous oxide) into the atmosphere. Fossil fuels are used for energy (electricity and heat), industry, transportation, and buildings. It is the primary cause, by far, of climate change.

- Agriculture, forestry, and other land use (AFOLU) are responsible for about one-fifth of global greenhouse gas emissions. This includes deforestation for agriculture and logging and livestock farming.

- Other activities contributing to greenhouse gas emissions include industrial processes like cement and chemical production.

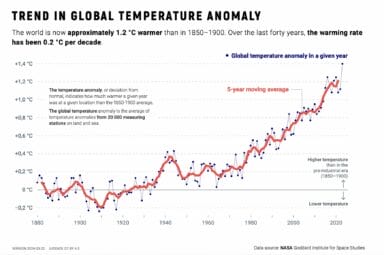

Source: Fakta o klimatu. Data source: NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies

Warming So Far

More than 99% of actively publishing climate scientists agree that human activity is overheating the planet and urgent action is needed.

Human-caused climate change has already warmed Earth 1.28 degrees Celsius, leading to more frequent and severe extreme weather events, sea-level rise, biodiversity loss, and more. Climate change is a global issue that is felt locally. Local impacts also include water scarcity, lower crop yields, infrastructure damage, and health issues, such as respiratory problems, longer allergy seasons, and the growth of vector-borne diseases such as malaria.

The global climate science body, the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, warns that exceeding 1.5 degrees C of warming will have exponentially more severe consequences, ushering in changes that will be impossible to stop; some changes will be irreversible.

Dig deeper: For more, see CCNow’s Climate Science 101 guide and this NDTV climate change video explainer.

Climate Impacts

Climate change impacts nearly everything. For example, drought can lead to less food production. Flooding can harm infrastructure. Extreme heat can hurt workers. The important thing to remember is that climate change affects all different areas of life and these impacts are interconnected. This section focuses on the science behind worsening extreme weather and how reporters can accurately and efficiently convey climate change’s impact on these events. Journalists are welcome to use the language below, which was adapted with permission from toolkits by Climate Central, in their reporting.

Heat and heatwaves. Heatwaves are getting hotter and longer. The increase in extreme heat is a result of our warming planet, as rising greenhouse gas emissions trap more heat in the atmosphere.

Heavy rain and flooding. Since warmer air holds more moisture, many regions are experiencing heavier rainfall or, when it’s cold enough, heavier snowfalls. This also increases the risk of flooding.

Coastal flooding. Coastal flooding is on the rise for two reasons. One, as the world warms, glaciers and ice sheets melt, increasing the amount of water in the oceans. Two, when water warms it expands.

Drought. Rising global temperatures increase the risk of drought. As temperatures climb, evaporation increases, drying out the soil faster, making droughts worse. Parched ground is more likely to lead to flooding because overly dry soil absorbs less water. The lack of water absorption combined with excessive heat drives further evaporation, further worsening the drought — a vicious cycle.

Hurricanes. Hurricanes are fueled by warm ocean waters. As climate change increases ocean temperatures, hurricanes have become more destructive, producing heavier rain and a higher storm surge. Warmer oceans cause hurricanes to intensify more rapidly, making them less predictable.

Wildfires. More frequent hot, dry, and windy conditions contribute to more wildfires. Dry winters, early-onset springs, and drier soil turn trees into kindling for wildfires.

Agriculture. Extreme weather is making it more challenging to grow food, as flooding, drought, and more take their toll. The problem is expected to worsen.

Dig deeper: See CCNow’s Extreme Weather Guide for more on the climate science behind these disasters.

Connecting Climate in Your Reporting

Extreme Weather

Climate change is making extreme weather more common and more severe. It’s critical to explain the climate connection in your reporting so audiences understand its causes. Here’s scientifically vetted sample language for making the connection:

- Human-caused climate change isn’t solely to blame for extreme weather, but it supercharges normal weather patterns, like steroids.

- Scientists agree that climate change drives extreme weather like today’s record-breaking high temperatures.

- Heatwaves like this one are now more common and more intense as a result of human-caused climate change.

Scientists use attribution science to study the impact of climate change on extreme weather or related events. For example, an attribution study found that India’s 2022 deadly heat wave was made 30 times more likely due to climate change. Most such studies take time to complete, but some events, such as heatwaves, can be analyzed nearly in real-time because there’s so much historical temperature data.

Source: The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Climate.gov

As the above graph from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Climate.gov project illustrates, scientists’ confidence in attributing global warming to different specific extreme events varies. For example, scientists have higher confidence for heat events compared to wildfires.

Dig deeper: See CCNow’s guide Making the Climate Connection, with language journalists can use for connecting climate to specific events.

Beyond Extreme Weather

Everywhere you look there are climate stories and climate angles. Whenever you’re reporting a story connecting climate, help audiences understand its root cause. Here’s some sample language to emulate:

- “Burning of fossil fuels, and the resulting carbon emissions, have been linked to rising temperatures, and South Korea’s economy relies heavily on such fuels for growth.” – Reuters

- “The situation is only expected to worsen as the continued burning of fossil fuels emits gases that trap heat from the sun, amplifying temperatures.” – CBS News

- “Infection-spreading creatures such as mosquitoes and ticks are thriving on a planet warmed by a blanket of fossil fuel emissions.” – The Washington Post

Climate Solutions

There are many solutions for reducing climate change and its impacts. Overall, two types of actions are needed:

- Mitigation. Actions that slow down climate change by reducing the amount of heat-trapping emissions released into the atmosphere. Examples include replacing coal-fired power plants with wind and solar energy, adopting electric cars, and reducing demand for deforestation, for example by eating less meat.

- Adaptation. Actions that increase our resilience to climate impacts that can no longer be avoided. Examples include setting up cooling centers, building flood barriers, and running electrical wiring underground to reduce fire risk.

Government action

International. Governments are taking climate action on the international, national, and local level. But collectively, the world is not moving fast enough. The 2015 Paris Agreement is the most important international climate agreement, which nearly every country in the world has ratified. It aims to keep temperature rise below 2 degrees C, while striving to cap rise at 1.5 degrees C.

Each year, countries that have signed the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, founded in 1992, meet to discuss plans for climate action, progress so far, and more at a summit called the Conference of the Parties (COP). The Paris Agreement was adopted in 2015 at COP21. Another historic breakthrough happened at COP27 in 2022. For the first time, countries agreed to a “loss and damage” fund to provide assistance to developing nations enduring the worst climate impacts, even though they have emitted the least carbon emissions.

National and local. The urgency of the climate crisis is becoming increasingly clear globally, and countries are starting to take more action. In the US, for example, the Inflation Reduction Act, passed in 2022, is the country’s biggest ever climate investment. It allocates at least $370 billion in subsidies, tax credits, and more over 10 years to help the country shift to cleaner energy. In 2021, the European Green Deal, aimed at reducing emissions by at least 55% by 2030, came into effect. China adopted its 1+N climate policy in 2021, as part of its goal to reach peak emissions in 2030 and carbon neutrality (where the total amount of carbon emitted equals the amount of emissions removed) in 2060. Many local governments are also taking climate action.

Dig deeper: See more on covering climate solutions related to politics, business, economics, technology, culture, and more in CCNow and Solution Journalism Network’s Climate Solutions Reporting Guide.

It’s Journalism, Not Activism

It’s not partisanship, or activism, to cover climate change. Climate change, and the need to act on it, is grounded in scientific consensus. We’ve heard from some newsrooms that they hesitate to cover climate and politics, fearing accusations of activism. This reluctance is fueled in part by campaigns and organizations funded by fossil fuel interests, which have either downplayed or denied climate change for decades. By sowing doubt about the scientific consensus, these efforts reinforce the misconception that climate coverage is activist-driven.

The pushback should be familiar to journalists. In pivotal moments throughout history, newsrooms have faced scrutiny for reporting uncomfortable truths, such as revealing government lies about troop deaths in Vietnam, documenting the Civil Rights struggle, or uncovering the Watergate scandal. This reporting wasn’t popular at the time, but they are held up in retrospect as some of journalism’s greatest moments.

Covering activists, critically and fairly, is part of covering the climate story. Resist the temptation to focus on the drama and the atmospherics. Engage instead in what the activists are saying, and what the people attending the protests are asking for. (For a good example on how to do that, see this piece from NBC’s Chase Cain in which he covers a climate protest in New York City.)

Tips for Reporting on Climate Change

There are strong climate angles that will resonate with audiences no matter what your reporting specialty is — politics, business, health, housing, education, food, national security, entertainment, sports, and more. For reporting prompts to help kickstart your coverage, see CCNow’s guide Covering Climate Across Beats. Below we look at some best climate reporting practices and pitfalls to avoid.

Best Practices

Drawing the climate connection in your reporting and including solutions when possible is the foundation of good climate journalism.

- Know your audience. Understanding audiences’ beliefs and feelings about climate change helps journalists to deliver stories that resonate and build trust. So, meet audiences where they are — and keep listening for how their views might change as their exposure to the climate story increases. To learn about audiences’ feelings about climate change, see Yale Climate Opinion Maps (US) and International Public Opinion on Climate Change (global).

- Center climate justice. The world’s poorest countries have contributed the least to climate change, but are the most vulnerable to its impacts. Within countries, marginalized groups generally suffer first and worst from climate change. It is critical to include the voices of those on the frontlines of climate change. People who have had to deal with the harshest consequences of climate change thus far have also had to become innovators in the climate fight. Indigenous peoples who have been environmental protectors for time immemorial are critical in the fight against climate change. For more see CCNow’s guide, Climate Justice.

- Humanize and localize the story. Climate change is a huge, global story, but, at its core, it’s a story about ordinary people and their daily lives. Audiences want coverage that reflects this, including first-hand perspectives on how people are experiencing climate change and what they can do about it. But climate change manifests differently in different places, so it’s vital that reporting illuminates the specific ways climate change unfolds locally.

- Include solutions. Many audiences don’t know that we already have most of the knowledge and technologies needed to solve climate change. Action is what’s needed, and fast. Reporting on solutions is not only an antidote to doomscrolling, it also helps people make more informed decisions. It’s not advocacy or activism; it is rigorous, fact-based reporting.

Pitfalls to Avoid

- Don’t get spun. Politicians, CEOs, and other powerful interests always have an agenda when they speak to the press. The fossil fuel industry’s decades of peddling climate disinformation are an egregious case in point. To avoid getting played, do your homework: Research their previous public statements, ask vetted experts where the truth lies, and then don’t be afraid to push back. See CCNow’s guide 10 Climate Change Myths Debunked for more common myths, and how to refute them.

- Beware of greenwashing. Companies and governments are waking up to public demands for eco-conscious practices. Pledges to “go green,” however, often amount to little more than marketing campaigns that obscure business as usual. Be fair but skeptical of grand promises about “sustainable” products and “net-zero” emissions, especially from companies, such as oil and gas companies, that historically have been a big part of the problem.

- Do not platform climate deniers. Platforming climate deniers in an effort to “balance” our coverage not only misleads the public, it is inaccurate. There is simply no good-faith argument against climate science. Where climate denialism cannot be avoided — if it comes from the highest levels of government, for example — responsible journalistic framing will make clear that the claim is false, if not rooted in bad faith.

- Avoid jargon. While it’s important for journalists to know climate science basics, take care to avoid jargon. Use simple, clear language, avoiding acronyms and using anecdotes to explain climate science when needed.

Dig deeper: For more tips on reporting the climate story, see CCNow’s Best Practices for Climate Journalism.

Getting Started and Ongoing Support

Climate isn’t a topic just for environmental reporters. It’s essential that every reporter explore climate angles on their beat. Don’t be intimidated by the science. A good understanding of the basics, many of which are covered in this guide, will take you far.

As you start integrating climate into your coverage, find additional support here:

- Join CCNow’s Community Slack, a platform with 2,000+ journalists who share questions, stories, and support. Note: Join CCNow as an individual member (it’s free) to gain access to Slack and other benefits.

- Sign up for our weekly and biweekly newsletters. They’re designed to support journalists and newsrooms with story ideas, reporting tips, and more.

- Attend CCNow’s Talking Shop and press briefing webinars.

- Check out CCNow’s Resource Hub, which includes our own reporting guides, as well as curated resources from authoritative sources.

- Follow us on LinkedIn, Instagram, and Twitter to get regular alerts about upcoming events, reporting tips, noteworthy stories, and more.

As you report, remember that Covering Climate Now is here to help journalists like you! Be sure to share your stories with us and submit your journalism to our annual Covering Climate Now Journalism Awards.